Immune checkpoint inhibitors are a type of cancer treatment that help the immune system’s T cells recognize and attack tumors. But these immunotherapy drugs aren’t effective against all cancers. In a study published today in Science Advances, University of Pittsburgh and UPMC researchers reveal how certain cells drive immunotherapy resistance in a mouse model of ovarian cancer and show that targeting a signaling pathway in these cells improved tumor responses to immunotherapy.

Senior author Ronald Buckanovich, M.D., Ph.D., professor of medicine at Pitt and co-director of the Women’s Cancer Research Center—a collaboration between UPMC Hillman Cancer Center and Magee-Womens Research Institute—discusses the significance of these findings and outlines how this research is informing a clinical trial for patients with ovarian cancer.

What is the background for this study?

RB: Immunotherapy can be very effective for patients with many different cancers, such as melanoma, head and neck cancer, and lung cancer. However, immunotherapy has worked relatively poorly in ovarian cancer: Only about 10 percent of patients gain a benefit, and that benefit tends to be less substantial than for patients with other tumor types. The goal of this study was to understand why ovarian cancer is resistant to immunotherapy and determine if we could develop new therapeutic approaches to increase the effectiveness of immunotherapy.

Can you describe the key findings of this study?

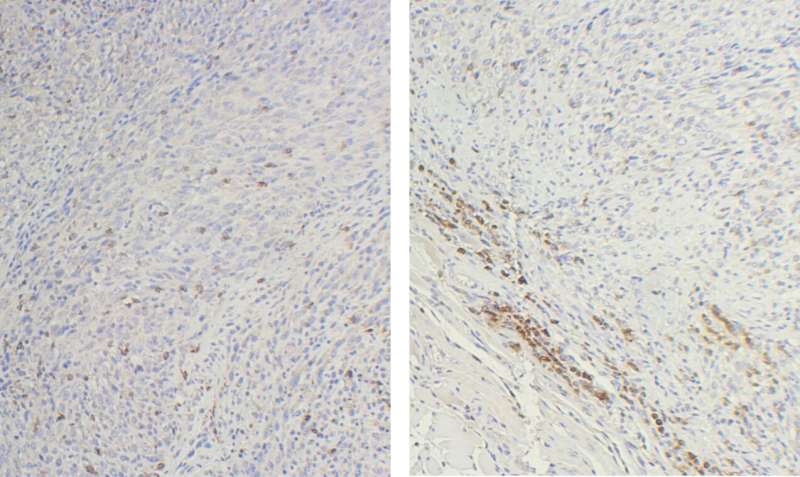

RB: We found that healthy, non-cancer cells, known as mesenchymal stem cells (MSCs), under the influence of the cancer cells, essentially create a barrier that prevents immune cells from entering the tumor. In cancer, we call this “tumor immune exclusion.” Furthermore, MSCs recruit and promote the generation of other immunosuppressive cells to inactivate any immune cells that can penetrate the barrier. Combined, this prevents immune cells from doing their jobs and killing cancer cells, even in the presence of immune-stimulating therapy. In short, if you can’t get to work, you can’t do your job. Imagine firefighters with the best firefighting equipment available—if they cannot get to the fire due to closed roads, they will be unable to put out the fire.

However, we found that inhibition of a signaling pathway known as the hedgehog pathway can prevent MSCs from establishing the immune barrier and reverse tumor immune exclusion. Importantly, we showed that clinically available hedgehog pathway inhibitors could restore the activity of immune therapy in otherwise immunotherapy-resistant ovarian cancer models.

What are the implications of these findings?

RB: These findings have several important clinical implications. First, this study strongly implicates MSCs as an important therapeutic target for immune therapy in ovarian cancer patients. Furthermore, we identified other potential therapeutic targets that could be contributing to immunosuppression in ovarian cancer patients. One protein— the TGF beta-induced protein—was found to predict a poor response to immunotherapy. We are currently developing new therapies targeting this protein.

What are the next steps for this research?

RB: One of the reasons I am so excited about this study is that it will directly lead to a new clinical trial for our patients with ovarian cancer. In partnership with Genentech, which will provide the hedgehog inhibitor and immunotherapy agent, we plan to launch a new clinical trial to determine if a hedgehog inhibitor can improve the benefits of immunotherapy in patients with therapy-resistant ovarian cancer. These are patients who otherwise have few treatment options. I am hopeful that this approach could have a significant benefit for these patients. We hope to start this trial sometime in the spring.