Muscular dystrophy describes a group of genetic diseases in which muscles progressively weaken and degenerate, with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) being the most common. There are no curative treatments for DMD, and available drugs for the most part delay the progression to extend the patient’s quality of life. A new study seen in Biomedicines by CiRA Assistant Professor Tomoya Uchimura and Associate Professor Hidetoshi Sakurai, both of whom join T-CiRA in collaboration with Takeda Pharmaceutical Company Limited (Takeda), uses iPS cells to show that drugs acting on store-operated calcium channels can extend the contractile function of muscles. The results reveal these channels are a new drug target for DMD treatments.

Along with being the most common muscle dystrophy, DMD is also the most well studied. It is marked by mutations in the protein dystrophin, whose dysfunction or loss results in injury to muscles when they contract and relax. Ultimately, patients grow weak and eventually are unable to breathe without artificial respiration. While gene therapies that correct the mutation are the holy grail in therapeutic research for DMD, drug treatments are thought easier to achieve.

Calcium is good for keeping bones strong. It is also essential for muscles. Muscle contractions depend on a surge of calcium ions being released in muscle cells. However, an overload of these ions can be deleterious and is commonly associated with DMD, explains Sakurai.

“It is widely accepted that calcium overload regulates the DMD pathogenesis. What we don’t know is if modulating calcium overload has therapeutic effects,” he said. One reason, he added, was the lack of experimental drug compounds, which is one of the reasons why Sakurai and Uchimura worked with Takeda: to access its large drug library.

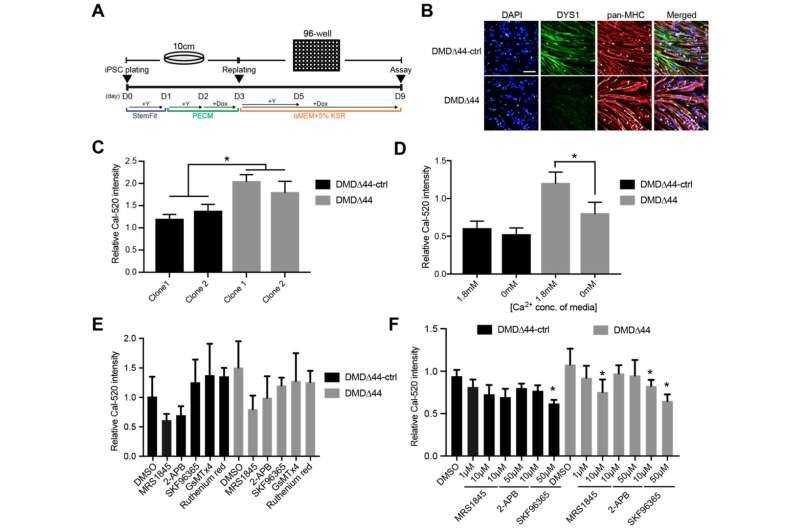

After confirming that muscle cells made from the iPS cells of a DMD patient showed calcium overloading, the two scientists screened for drugs that inhibit store-operated calcium channels.

“There are multiple calcium channels in muscles cells, but the easiest to target are store-operated calcium channels, because they are on the extracellular membrane,” said Uchimura.

They found several store-operated calcium channel inhibitors blocked the calcium overload and extended the contractile function of muscle cells for at least two weeks. In contrast, muscle cells without the drug treatment showed failing contractile function within a few days.

The inhibitors specifically blocked one type of store-operated calcium channel.

“The STIM1-Orai1 complex is the major store-operated calcium channel,” said Uchimura. “Our results suggested it is the major regulator of calcium overload in DMD and a potential drug target.”

Kyoto University