Mutations in a crucial gene are the key reason that chemotherapy fails in some patients with blood cancer, a study by Nanyang Technological University, Singapore (NTU Singapore) and Singapore General Hospital (SGH) has found.

Lymphoma, a type of blood cancer, is the fifth most common cancer among males and the sixth most common cancer for females in Singapore, according to latest data from the Singapore Cancer Registry. Broadly divided into Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the cancer is often treated with chemotherapy regimens.

However, majority of patients with aggressive forms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma do not respond to traditional therapy, and a sub-group of patients who respond initially go on to relapse and progress to fatal outcomes.

To unravel the puzzle of why chemotherapy fails in certain patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma, the research team led by Assistant Professor Navin Verma at NTU’s Lee Kong Chian School of Medicine (LKCMedicine) and Assistant Professor Nicholas Grigoropoulos, senior consultant from the Department of Haematology at SGH, scrutinized the publicly available genetic database of over a thousand UK patients. In addition, the research team analyzed a total of 167 non-Hodgkin lymphoma specimens from patients in the UK in collaboration with research groups at the University of Cambridge, UK.

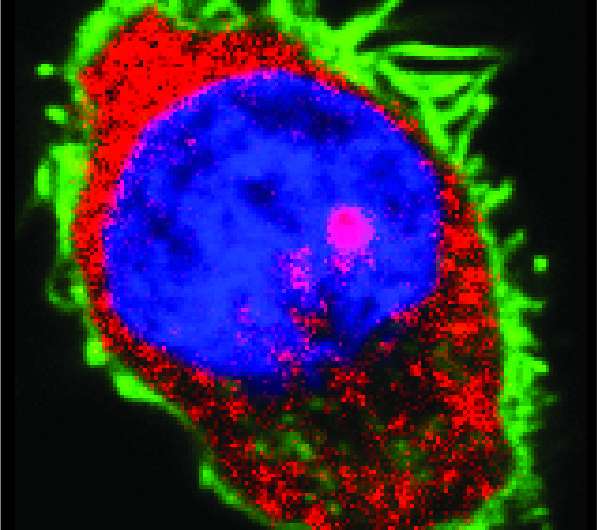

Through advanced gene sequencing technology, the research team mapped cancer-causing gene abnormalities from samples of patients whose chemotherapy failed. They found that mutations in the gene DDX3X—a type of protein responsible for processing and transmitting signals for cell growth—is the possible culprit behind cancer cells’ resilience. This was later confirmed using cutting-edge molecular techniques.

The team combined their genetic data and those from previous studies and found through advanced analysis that lymphoma patients with DDX3X mutations had a significantly lower survival rate than those without such mutations. They also found that DDX3X mutations cause increased STAT activity—a type of signaling mechanism that allows cancer cells to survive.

Upon further investigations, the team tested the STAT3 inhibitors—a substance and member of the STAT family that interferes with biologic activity including growth and proliferation—and discovered that these inhibitors killed lymphoma cells with DDX3X mutation (or altered DDX3X) more effectively than standard chemotherapy agents.

Although further research is needed, these findings provide hope that new and better drugs could be developed to block STAT activity and therefore improve the chances of survival for non-Hodgkin lymphoma patients with DDX3X mutations. Clinicians may in future be able to test for such mutations to have a better gauge of chemotherapy outcomes for patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Asst Prof Navin said, “Now that we know DDX3X mutations are what make some cancer cells difficult to kill with chemotherapy, it is possible to identify patients with such mutations through lab tests before treatment starts. Early identification will allow clinicians to have a better understanding of general chemotherapy outcome for this group of cancer patients and enable them to offer personalized therapy from the get-go, buying precious time that would otherwise be spent on futile chemotherapy.”

Published in the scientific journal Molecular Cancer in October 2021, the findings shed light on aggressive forms of non-Hodgkin lymphoma and provide insights into possible new therapy options for this group of patients with poor chances of survival.

What is DDX3X?

Located on the X chromosome, the gene DDX3X processes cell information and transmits signals for cell growth. While past research studies have associated the gene’s involvement in many types of cancer, its role in non-Hodgkin lymphoma has not been studied at detailed molecular levels until now.

Asst Prof Grigoropoulos said, “We leveraged our extensive clinical experience in treating patients with lymphoma at the Singapore General Hospital to design and execute the research and proved that DDX3X mutation is associated with chemotherapy resistance. But more needs to be done. We are now continuing our research efforts and actively developing new drugs as well as diagnostics to help those with DDX3X mutations, not only in lymphoma, but other common cancers as well.”

First author Atish Kizhakeyil, a Ph.D. student at LKCMedicine said, “Previously, the exact role of DDX3X gene in lymphoma progression was less known. I believe that our findings on the loss of function of DDX3X would help in improving treatment outcomes of lymphoma patients with DDX3X alteration.”

Professor Dermot Kelleher, dean of the faculty of medicine and vice-president, health at the University of British Columbia in Vancouver, Canada, who was not involved in the study, said, “Understanding more about this gene and what specific changes DDX3X mutations lead to the aggressiveness and chemoresistance in lymphoma subtypes will help us to fine tune treatments, which would provide these patients with mutated gene the best possible chance of survival.”

Highlighting the significance of being able to access and use non-Hodgkin lymphoma specimens for their study, the research team said without these specimens, research hypotheses and theories will remain as they are and there will be no treatment or a better way of diagnosing cancers.

The researchers are looking to conduct further research that could lead to the development of new cancer drugs based on their insights into DDX3X, which has the potential to be used as a target for a better cure for lymphoma and beyond.

Nanyang Technological University