It should come as no surprise that as we age, physical activity becomes increasingly valuable in staving off non-communicable diseases like diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure, as well as diminished muscle tone and bone density—major issues for longevity and quality of life.

Some of us have more risk factors than others. In a new study in the journal AIDS Patient Care and STDs, Professor John B. Jemmott III worked with one of the highest risk groups for these chronic diseases: African American men over 40 who live with HIV. And while anti-retroviral drugs often taken by these men have increased their lifespans, research indicates the drugs also make them more vulnerable to the non-communicable diseases associated with aging.

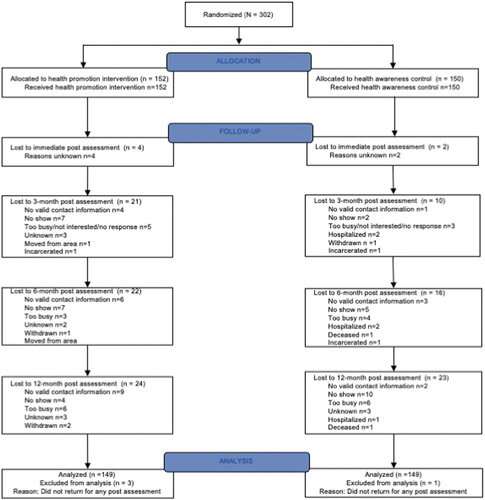

In a randomized controlled trial with 302 participants, Jemmott and his research team showed that three sessions of health promotion based on social cognitive theory and the reasoned action approach increased the odds that these men, who on average have low rates of physical exercise, would meet federal guidelines for physical activity in both aerobic exercise and muscle strengthening. Even a full year after the sessions, their physical activity levels were higher than the control group.

The men who completed the intervention also experienced significant increases in self-reported aerobic and muscle strengthening exercise.

While there have been several research-based attempts to increase physical activity in African American men over 40 living with HIV, Jemmott’s study was the first to succeed.

Jemmott, the Kenneth B. Clark Professor of Communication and Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania, credits the success to the intervention’s tailored and interactive approach.

“We tried to understand the common barriers to physical activity for this population—what makes it hard? What would make it easier to incorporate into their lifestyle?” says Jemmott. “For example, many of them are in poor physical shape, so we showed them exercises they could do while sitting in a chair.”

With a single facilitator, participants engaged in interactive activities, brainstorming, physical exercise, watching videos and playing games like “Health Jeopardy” and “Health Basketball” to reinforce the information. They received a pedometer to measure their steps and a DVD showing exercises at different levels. They also identified people in their support structure and wrote a letter to themselves, promising to engage in healthy behavior, including reasons and strategies for doing so. Six weeks after the program ended, facilitators mailed them their letters.

While the intervention’s three three-hour visits had a structured curriculum—nutrition in the first session, exercise in the second, and “managing your future health” in the third—it was also highly collaborative. Groups discussed their personal barriers to exercising, and then problem-solved together. Ideas that emerged were different for different groups.

The three sessions were designed using social cognitive theory, whereby the outcome people expect impacts whether they will engage in a given behavior. It also hinges upon self-efficacy—whether the participants believe they have the tools to succeed, despite the significant barriers they face, including unstable housing, alcohol dependency, substance use, and low incomes. These men living with HIV were encouraged to believe they could increase their physical activity, and that it would have a measurable benefit to their lives. They were also given the knowledge and skills necessary.

The researchers hope that this relatively brief, flexible curriculum can be adopted by community organizations that serve people with HIV, with the goal of increasing exercise and decreasing non-communicable disease. It may also be even more beneficial when men living with HIV encounter this material before the age of 40.

The paper, “Effects of a Health Promotion Intervention on Physical Activity in African American Men Living with HIV: Randomized Control Trial” was published in the October issue of AIDS Patient Care and STDs.

Julie Sloane, University of Pennsylvania