Facing addiction can seem insurmountable—especially when opioids are involved. Doubts of one’s ability to stay substance-free; fears around judgment from family, friends, and society; and efforts to manage addiction while continuing balancing life’s responsibilities can compound. Now, imagine on top of that, you find out you are pregnant, and now you really want to have a healthy baby but know it could be extra difficult. Will my baby be okay? Should I try to quit cold turkey? How will my doctor react if they find out?

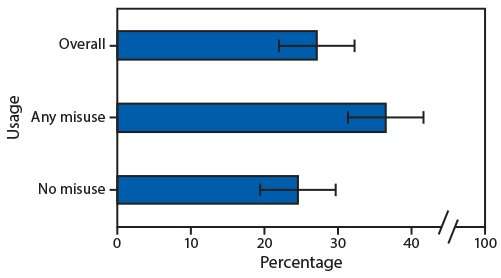

These are the situations and questions presented to thousands of Americans every year. According to CDC research published last year from self-reported data, roughly 7 percent of pregnant people reported they took opioid drugs during pregnancy, and of those 7 percent, one in five reported inappropriate opioid use—taking an amount or substance not prescribed by a clinician.

In response to seeing patients with these types of challenges at Penn Family Care, Ayiti-Carmel Maharaj-Best, MD, Navid Roder, MD, and Judy Chertok, MD, all assistant professors of Clinical Family Medicine and Community Health in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, and their team established the Penn PROUD (Perinatal Resources for Opioid Use Disorder) Clinic at Penn Family Care last summer. Together, the team provides both primary care and prenatal care to expectant patients before, during, and after birth as well as care for the newborn. In just months, the clinic has cared for dozens of pregnant patients with OUD and is poised to care for many more.

Some patients who receive care at the PROUD Clinic are identified through screening for substance use during their primary care or prenatal visits. Other patients come specifically seeking help for OUD.

Medication for opioid use disorder

While it might seem that stopping “cold turkey” might be the best way to prevent bad outcomes during pregnancy, research has shown that this approach is not necessarily the safest, said Maharaj-Best. Withdrawal can actually lead to stress and miscarriage. “Rates of relapse are high especially in stressful times like during pregnancy and postpartum. This puts patients at a high risk for overdose or possibly death, which is where medication can be helpful,” she said.

Instead, in most cases, the PROUD Clinic starts patients on doses of medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD), most commonly suboxone. “Suboxone decreases cravings and blocks the symptoms of withdrawal but does not have the same potential for abuse and can decrease the likelihood of overdose,” said Roder. Research has shown that these medications are safe to use in pregnancy and breastfeeding.

Monitoring the babies

Untreated in pregnancy is associated with worse birth outcomes, including premature birth, low birth weight, and stillbirth—all outcomes the PROUD Clinic seeks to prevent through an interdisciplinary approach and a keen eye for potential complications. This may require more frequent visits as well as ultrasounds and collaboration with additional behavioral and medical professionals.

During the first five days of life, babies are observed for signs of neonatal opioid withdrawal syndrome (NOWS), a condition in newborns that mirrors opioid withdrawal in adults. Babies are monitored for signs such as shaking, sweating, trouble feeding, vomiting, and diarrhea, which can often be alleviated with human contact, but in some cases, requires medication and fluids.

“In those first days of a baby’s life, we really encourage parents to be present with their babies, because just being held, rocked, and soothed has actually been shown to decrease those symptoms,” said Maharaj-Best.

Mental health support

Opioid use disorder can easily compound anxiety and depression that are already a concern in any pregnancy, said Roder. “Pregnancy is a source of stress for any birth parent, and the addition of struggling with addiction just adds to that stress.”

At the PROUD Clinic, and in general at Penn Family Care, patients are screened for mental health conditions and supported with integrated care. Patients can be seen by Licensed-Clinical Social Workers, can be prescribed medication, and in some cases, are referred to other mental-health practitioners for additional care.

Additionally, patients with OUD are connected with Certified Recovery Specialists, trained professionals who have themselves battled addiction and understand first-hand the challenges of achieving and maintaining sobriety.

Combined appointments

As most parents will attest, when a baby is born, the baby’s care, well-being, and well … everything … supersedes all other needs. But that can come at a cost to the new parents’ health.

“The first few months after having a baby is a hectic time, and many patients never make it to their postpartum visit,” said Maharaj-Best. “However, our data shows that the birth parent is present at roughly 90 percent of newborn appointments in the first year. Being family doctors, we have a unique opportunity to use the newborn visits to deliver care for parents as well.”

In order to accommodate and ensure recently-pregnant patients and their babies both receive medical care, Penn Family Care, including the PROUD Clinic, provides combined appointments where both babies and their parents receive care during the same appointment.

“Another benefit of this approach is that you have one care team that understands the patient’s family, situation, and needs,” said Roder. “Practitioners in Family Medicine know well how one’s family can really impact every member’s health. Having one doctor or one care team that fully knows the ins and outs of a family can know what to monitor and know how to come up with interventions that are more likely to work. Family visits are always welcome at Penn Family Care.”

Alex Gardner, University of Pennsylvania