New research led by the University of Bristol has found the protein p53 plays a key role in epithelial migration and tissue repair. The findings could improve our understanding of the processes used by cells to repair tissues, and be used to identify interventions that could accelerate and improve wound repair.

Epithelial tissues are the linings that protect the body’s external skin and internal cavities, and their ability to repair themself is important. It is known that wounded epithelia repair themself thanks to the ability of the remaining cells to start migrating, collectively, to seal the breach. Specialized migratory cells called leader cells arise from damaged epithelia, promoting epithelial migration. However, it’s unclear what molecules and signals in epithelial cells make them become migratory leaders and how some wounded cells develop leader behavior whilst some do not.

The study, published in Science, found that, when epithelial cells are damaged, the damage activates a molecular program that turns cells into migratory leader cells so that the breach can be repaired quickly. The same molecular program also makes sure that these highly migratory cells are removed when the breach is closed, so that the tissue restores its normal epithelial tissue structure.Play00:0000:05MuteSettingsPIPEnter fullscreenPlayTime lapse video of a model wound in vitro. A leader cell emerging from the population drives the collective migration of the followers into the gap to seal the breach. Once the tissue has been repaired the leader cell is surrounded by its neighbours and eliminated. Credit: University of Bristol

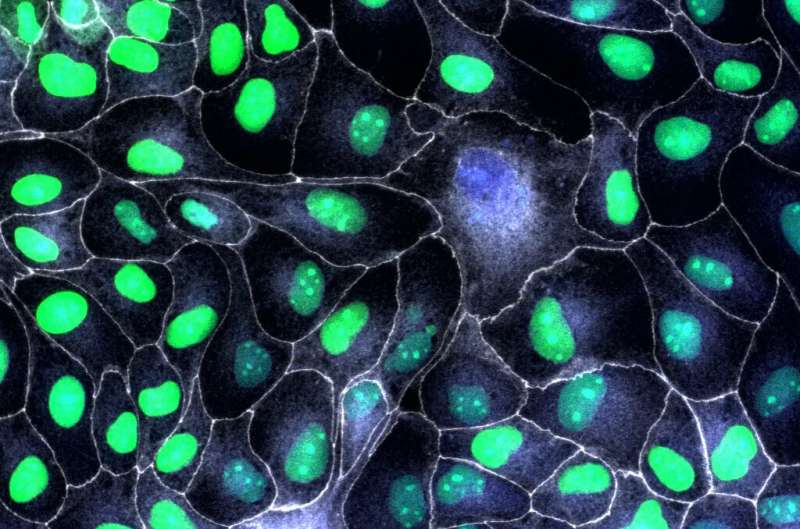

Using a simplified model of a wound, epithelial sheets that were scratched in vitro to injure the epithelial monolayer, the researchers identified the molecular signal that makes leader cells emerge.

The study found that, following injury, cells at the border of the epithelial gap elevate p53 and p21, suggesting that the injury triggers the migratory program. Once the breach was repaired, leader cells were eliminated from the population by their healthy epithelial neighbors. The cells damaged by the wound were able to cause wound closure, but are then sacrificed to maintain a functional tissue with normal epithelial morphology.

Eugenia Piddini, Professorial Research Fellow in Cell Biology and Wellcome Trust Senior Research Fellow in the School of Cellular and Molecular Medicine (CMM) at the University of Bristol and lead senior author of this work, said: “Our findings improve our understanding of the mechanisms used by cells to repair tissues, and could be used to develop systems that accelerate wound healing.

“p53 plays two critical roles in epithelial repair. It starts leader driven epithelial closure and once the epithelium has been repaired, p53 induces leader cell clearance.”

Dr. Giulia Pilia, Research Associate in CMM at the University of Bristol and co-first author, added: “Collective migration is important in other areas, for example in cancer, where groups of cells move together from the primary tumor to create metastases. It would be important to know if the same proteins that we identified in the wound model are at play in this situation, so that current therapeutic treatments could be modified.”

Next steps for the research will be to test whether the mechanisms that have been found in the in vitro epithelium also apply in vivo. If this is the case, the research team would like to test if they can selectively and safely induce leaders in vivo, to promote migration and tissue repair. This new-found knowledge of how leaders work could also be used to develop new therapeutic approaches that could help block the unwanted migration of metastatic cells.

University of Bristol