Family or species, color or size, grouping things into categories is efficient for the brain. But those categories can also create biases in perception, studies show.

People perceive things that are in the same group as more similar to each other than things outside of that group, even if they’re equally dissimilar. And those category-based biases are reflected in widespread patterns of brain activity, new research from Dasa Zeithamova’s lab at the University of Oregon shows.

Her team found that category labels could change the way people viewed faces after even just a few exposures. “It’s surprising that this happens so rapidly,” Zeithamova said. She and former graduate student Stefania Ashby reported their findings Feb. 2 in The Journal of Neuroscience.

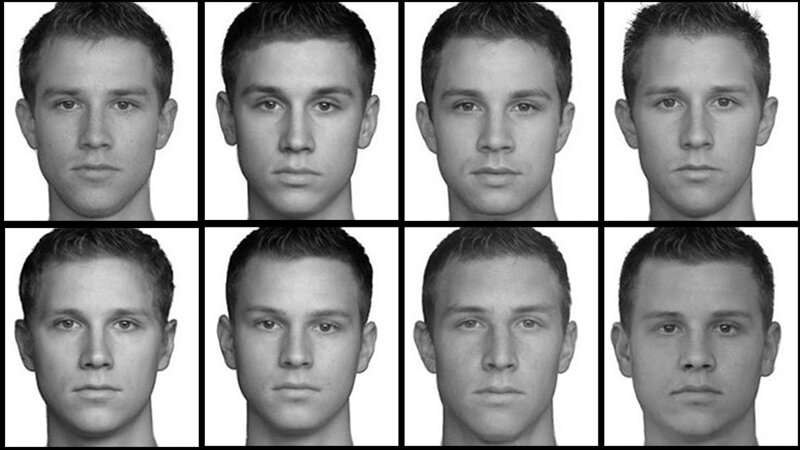

Zeithamova and Ashby used a computer program to blend different pairs of face photos together. They created a library of new face pictures, some of which shared a “parent” face and therefore had subtle similarities in facial features.

Some faces sharing a parent face were given the same last name, while others were categorized into different families. Over a series of trials, participants learned first and last names for each of the faces.

In a previous experiment, Zeithamova’s lab found that participants rated faces as more similar when they were associated with the same last name. In this new work, she studied participants’ brain activity while they completed a similar task. This time around, the participants didn’t consciously rate the same-family faces as more similar. But the biases still showed up widely in their brains.

“We saw that the brain representations became biased to highlight the commonalities among things that happen to share a label,” Zeithamova said, with activity patterns more similar when people saw faces in the same family.

When people saw face photos that shared a parent face but weren’t classified as part of the same family, brain activity was more distinct.

“We suspected that maybe a few regions would show this bias, but instead we found it everywhere,” she said.

When people have certain categories or concepts in mind, they focus on specific relevant features and tune out others. But to succeed at the task at hand here, participants also needed to pay attention to differences between the faces; they had to be able to tell Peter Miller apart from Kyle Miller. Instead, just the presence of category labels biased the brain, and “people discounted the information they actually need for the task,” Zeithamova said.

It remains to be seen how far the finding generalizes. Next, Zeithamova wants to figure out whether preexisting category labels also distort the way the brain interprets new faces and whether people can update categories in the face of new information.

Laurel Hamers, University of Oregon