A research team around Dr. Andreas Weltin, Dr. Jochen Kieninger and Johannes Dornhof from the Department of Microsystems Engineering (IMTEK) at the University of Freiburg has developed a system that, among other things, makes it possible to study the development of tumor cells outside the human body in a three-dimensional environment. “We have realized an organ-on-chip system that can measure and control the culture conditions and metabolic rates of the cells at any time via microsensors. Until now, this has been only insufficiently possible in 3D cell cultures,” Weltin says. The system was developed in collaboration with the Molecular Gynecology group of the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics at RWTH Aachen University Hospital. In the future, patient-derived cells in organ-on-chip systems could enable personalized cancer therapy. The scientists’ work was published in the scientific journal Lab on a Chip.

Integrated sensors measure cellular metabolites

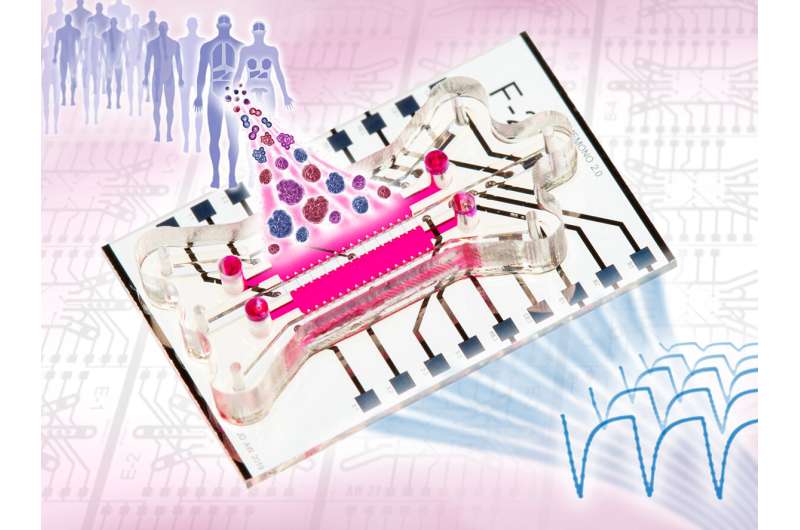

In organ-on-chip systems, three-dimensional tissue models are interconnected by an artificial circuit in such a way that they act like organs in miniature on a microchip. In this way, physiological processes—for example the growth of a tumor—can be reproduced and observed outside the human body. The research group created a chip design with integrated microsensors and microfluidics that can measure the cells’ metabolites directly in situ. In their system, the scientists grew breast cancer mini-tumors from individual stem cells and used electrochemical sensors to monitor cellular oxygen and glucose consumption and lactate production over a period of one week.

“Our platform enables the dynamic 3D culture of tumor organoids, whereas until now static 2D cultures have often been used, which can only recapitulate the complex microenvironment of a tumor to a limited extent,” says first author and Ph.D. student Johannes Dornhof. In addition, the chip system can also be used to examine the effect of drugs on cell metabolism—for example, the cellular effect of chemotherapeutic agents could be recorded quantitatively and in real time in the context of cancer research.

Patient-derived cells could enable personalized therapy

The use of the patient’s own stem cells makes it possible to replicate an original tumor outside the body. This could offer new opportunities for personalized therapy, for example with regard to possible resistance to certain chemotherapeutic agents, which is crucial in aggressive triple-negative breast cancer. In the future, it should be possible to initially test drugs for a patient in organ-on-a-chip systems for effectiveness and side effects.

“Our results underline the potential of integrating microsensors into organ-on-chip systems in cancer research and drug development—especially with regard to personalized medicine,” says Weltin. And Dr. Jochen Kieninger explains: “This work nicely demonstrates the importance of interdisciplinary research. Bringing together different engineering disciplines with biology and medicine was essential for success.”

University of Freiburg