Average daily COVID-19 cases and hospitalizations are continuing to fall in the U.S., an indicator that the omicron variant’s hold is weakening across the country.

Total confirmed cases reported Saturday barely exceeded 100,000, a sharp downturn from around 800,850 five weeks ago on Jan. 16, according to Johns Hopkins University data.

In New York, the number of cases went down by more than 50% over the last two weeks.

“I think what’s influencing the decline, of course, is that omicron is starting to run out of people to infect,” said Dr. Thomas Russo, professor and infectious disease chief at the University of Buffalo’s Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences.

COVID-19 hospitalizations are down from a national seven-day average of 146,534 on Jan. 20 to 80,185 the week ending in Feb 13, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID data tracker.

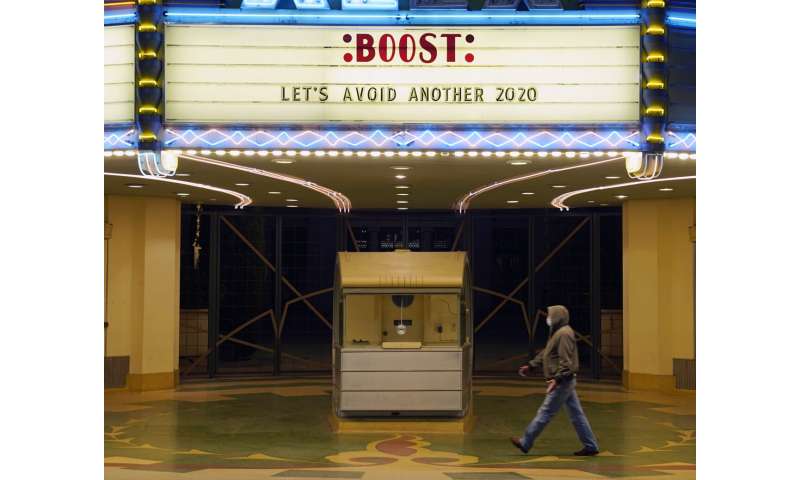

Public health experts say they are feeling hopeful that more declines are ahead and that the country is shifting from being in a pandemic to an ‘endemic’ that is more consistent and predictable. However, many expressed concern that vaccine uptick in the U.S. has still been below expectations, concerns that are exacerbated by the lifting of COVID-19 restrictions.

Dr. William Schaffner of Vanderbilt University’s School of Medicine said Sunday that the downturn in case numbers and hospitalizations is encouraging. He agreed that it likely has a lot to do with herd immunity.

“There are two sides to omicron’s coin,” he said. “The bad thing is that it can spread to a lot of people and make them mildly ill. The good thing is it can spread to a lot of people and make them mildly ill, because in doing so, it has created a lot of natural immunity.”

However, Schaffner said it’s much too early to “raise the banner of mission accomplished.” As a public health expert, he said he’ll be more comfortable if the decline sustains itself for another month or two.

“If I have a concern, it’s that taking off the interventions, the restrictions, may be happening with a bit more enthusiasm and speed than makes me comfortable,” he said. “My own little adage is, better to wear the mask for a month too long, than to take the mask off a month too soon and all of a sudden get another surge.”

Officials in many states are cutting back on restrictions, saying they are moving away from treating the coronavirus pandemic as a public health crisis and instead shifting to policy focused on prevention.

During a Friday news conference, Utah Gov. Spencer Cox announced that the state would be transitioning into what he called a “steady state” model starting in April in which Utah will close mass testing sites, report COVID-19 case counts on a more infrequent basis and advise residents to make personal choices to manage the risk of contracting the virus.

“Now, let me be clear, this is not the end of COVID, but it is the end—or rather the beginning—of treating COVID as we do other seasonal respiratory viruses,” the Republican said.

Also on Friday, Boston lifted the city’s proof of vaccine policy, which required patrons and staff of indoor spaces to show proof of vaccination.

“This news highlights the progress we’ve made in our fight against Covid-19 thanks to vaccines & boosters,” Boston Mayor Michelle Wu said via Twitter.

Dr. Amy Gordon Bono, a Nashville primary care physician, said now is not the time to lessen vaccination efforts, but to double down on them. In the spring of 2021 when vaccines were becoming more readily available, the U.S. was “eager to declare COVID independence,” she said. Then came the delta and omicron surges.

Bono, who attended medical school at Tulane University in New Orleans, said the U.S. should approach COVID like hurricane season.

“You have to learn to live with COVID and you have to learn from it,” she said.

One challenge is that each region has a unique landscape, she said. In the American South, for example, many restrictions have been lifted for a while or never existed in the first place. Yet it’s also a region with relatively lower vaccination rates.

“We’ve suffered so much and if there’s a way to help appease future suffering, it’s having a more vaccinated community,” she said.

In Buffalo, Russo said he sees two possible future outcomes. In one, the U.S. experiences a fairly quiet spring and summer while immunity is still strong. He said in that scenario, it’s likely immunity will wane and there will be a bump of new cases in the cooler months during flu season, but hopefully not a severe surge.

In the second—the one concerning public health experts—a new variant evolves and evades the immunity wall that was built up from both omicron infections and vaccinations.

“Whether such a variant can evolve is the big question, right?” he said. “That is the concern that we’ll have to see through. Omicron was the first version of that, and there is this sort of adage that ‘well, over time, viruses evolve to be less virulent,’ but that’s not really true. Viruses evolve to be able to infect us.”

Leah Willingham and Jonathan Mattise