Researchers have developed a new fluorescent label that gives a clearer picture of how DNA architecture is disrupted in cancer cells. The findings could improve cancer diagnoses for patients and classification of future cancer risk.

Published today in Science Advances, the study found that the DNA-binding dye performed well in processed clinical tissue samples and generated high-quality images via superresolution fluorescence microscopy.

“My lab is focused on developing microscopy techniques to visualize the invisible,” said senior author Yang Liu, Ph.D., associate professor of medicine and bioengineering at the University of Pittsburgh. “We are one of the first groups to explore the capabilities of superresolution microscopy in the clinical realm. Previously, we improved its throughput and robustness for analysis of clinical cancer samples. Now, we have a DNA dye that is easy to use, which solves another big problem in bringing this technology to patient care.”

Inside the cell’s nucleus, DNA strands are wound around proteins like beads on a string. Pathologists routinely use traditional light microscopes to visualize disruption to this DNA-protein complex, or chromatin, as a marker of cancer or precancerous lesions.

“Although we know that chromatin is changed at the molecular scale during cancer development, we haven’t been able to clearly see what those changes are. This has bothered me for more than 10 years,” said Liu, who is also a member of the UPMC Hillman Cancer Center. “To improve cancer diagnosis, we need tools to visualize nuclear structure at much greater resolution.”

In 2014, the Nobel Prize-winning invention of superresolution fluorescence microscopy was a major step towards making Liu’s vision reality. A molecule of interest is labeled with a special fluorescent dye that flashes on and off like a blinking star. Unlike traditional fluorescence microscopy, which uses labels that glow constantly, this approach involves switching on only a subset of the labels at each moment. When several images are overlayed, the complete picture can be reconstructed—at a much higher resolution than previously possible.

Until now, the problem was that fluorescent dyes didn’t work well on DNA or in processed clinical cancer samples. So, Liu and her team formulated a new label called Hoechst-Cy5 by combining the DNA-binding molecule Cy5 and a fluorescent dye called Hoechst with ideal blinking properties for superresolution microscopy.

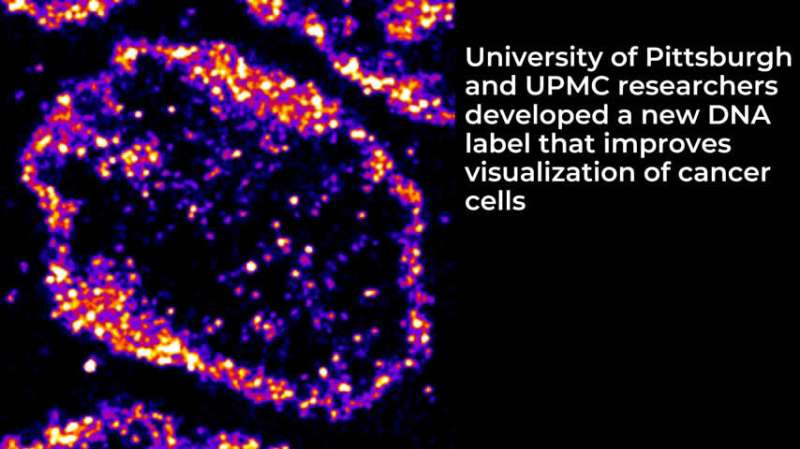

After showing that the new label produced higher resolution images than other dyes, the researchers compared colorectal tissue from normal, precancerous and cancerous lesions. In normal cells, chromatin is densely packed, especially at the edges of the nucleus. Condensed DNA glows brightly because a higher density of labels emits a stronger signal, while loosely packed chromatin produces a dimmer signal.

Play00:0001:22MuteSettingsPIPEnter fullscreen

The images show that as cancer progresses, chromatin becomes less densely packed, and the compact structure at the nuclear border is severely disrupted. While these findings indicate that the new label can distinguish normal tissue from precancerous and cancerous lesions, Liu said that superresolution microscopy is unlikely to replace traditional microscopes for such routine clinical diagnoses. Instead, this technology could shine in risk stratification.

“Early-stage lesions can have very different clinical outcomes,” said Liu. “Some people develop cancer very quickly, and others stay at the precursor stage for a long time. Stratifying cancer risk is a major challenge in cancer prevention.”

To see if chromatin structure could hold clues about future cancer risk, Liu and her team evaluated patients with Lynch syndrome, a heritable condition that increases the risk of several cancer types, including colon cancer. They looked at non-cancerous colorectal tissue from healthy people without Lynch syndrome and Lynch patients with or without a personal history of cancer.

The differences were striking. In Lynch patients who previously had colon cancer, chromatin was much less condensed than in healthy samples, suggesting that chromatin disruption could be an early sign of cancer development—even in tissue that looks completely normal to pathologists.

For Lynch patients without a personal history of cancer, some will go on to develop cancer, while others will not.

“We see a much larger spread in this group, which is very interesting,” said Liu. “Some patients resemble healthy controls, and some are closer to Lynch patients who previously had cancer. We think that patients with more open chromatin are those who are more likely to develop cancer. We need to follow these patients over time to measure outcomes, but we’re pretty excited that chromatin disruption in normal cells could potentially predict cancer risk.”

In future work, Liu and her team are interested in examining chromatin structure in endometrial tissue from Lynch patients, who also have elevated risk of endometrial cancer. The researchers also received funding recently to look at sputum samples from smokers for early detection of lung cancer.

Other authors who contributed to this study were Jianquan Xu, Ph.D., Xuejiao Sun, M.S., Hongqiang Ma, Ph.D., Rhonda M. Brand, Ph.D., Douglas Hartman, M.D., and Randall E. Brand, M.D., all of Pitt; and Mingfeng Bai, Ph.D., and Kwangho Kim, Ph.D., both of Vanderbilt University.

University of Pittsburgh