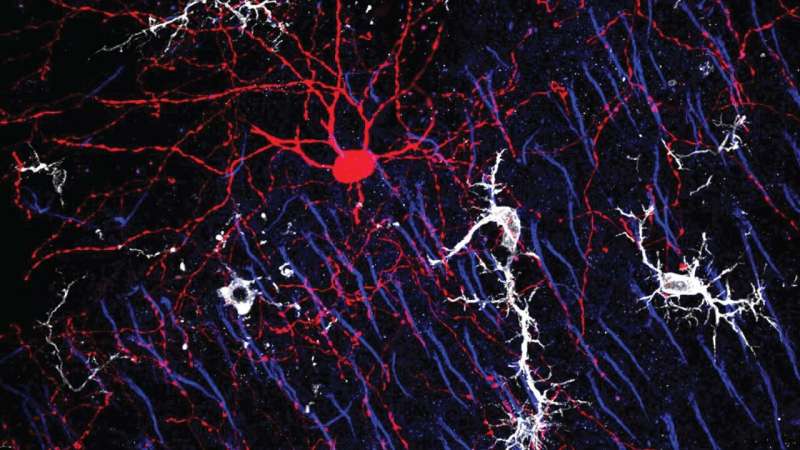

Microglia, the immune cells of the brain, are known for eating up unwanted items like germs and debris, much as their counterparts do in the rest of the body. In early childhood, certain microglia remove unneeded connections, or synapses, to shape the adult brain’s organized circuitry. Now, Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory (CSHL) Professor Linda Van Aelst has found that in mice, microglia also help neurons grow synapses critical to cognitive functioning.

“Most immune cells are known to target and eat—let’s call it garbage,” says Van Aelst. “But what we saw is the opposite. During a particular developmental time point, under normal physiological conditions, they did not eat any synapses that we saw, but helped the synapses form. That was quite a nice surprise.”

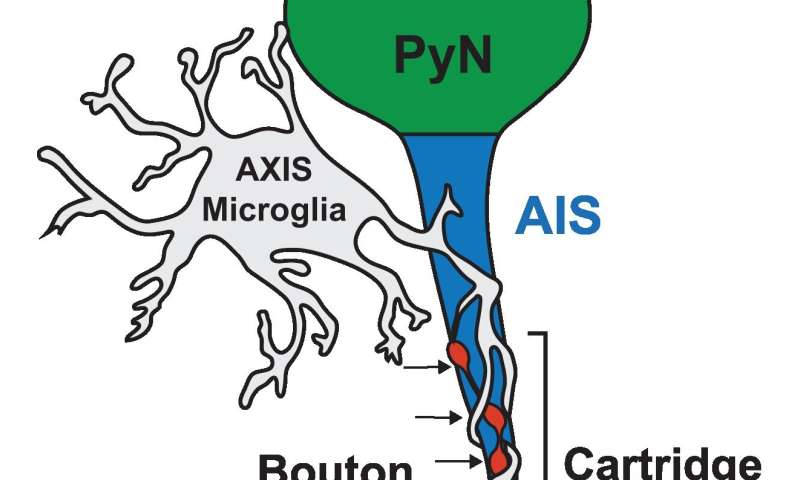

It was Van Aelst’s obsession with a rare type of inhibitory neuron called a chandelier cell that sparked her interest in microglia. Chandelier cells are named for the ornate branching shape of their nerve fibers. These structures make direct contact with the section of a target neuron that sets off its firing: the axonal initial segment (AIS). This unique synapse gives chandelier cells powerful control over the signaling of hundreds of neighboring neurons at once.

“These synapses are critical for chandelier cells to silence the excitatory neurons. Too much excitation can contribute to disorders like epilepsy, schizophrenia, and autism,” Van Aelst explains. She wondered what other cell types regulate the formation of such synapses.

Together with graduate students Nicholas Gallo and research assistant Artan Berisha, Van Aelst studied how microglia interact with chandelier cells. They found that microglia wrap their armlike processes around the synapse-forming structures of a chandelier cell and its target neuron, increasing proper synapse formation. These special embraces were more common in pups and young mice than in adults.

“And that was really cool,” she says. “This is the first time that microglia have been implicated in these unique synapses as a growth-promoting function.”

The team then tested what happens when microglia are impaired. “We saw that there were less microglia going to where chandelier cells make contact on the AIS,” Van Aelst says. “And we saw that fewer of these synapses formed.”

Microglia “are only one of the players that control synaptogenesis, but key players that people didn’t think of or expect,” she says. Ultimately, the researchers want to see if microglia could be recruited to help treat neurological disorders.

Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory