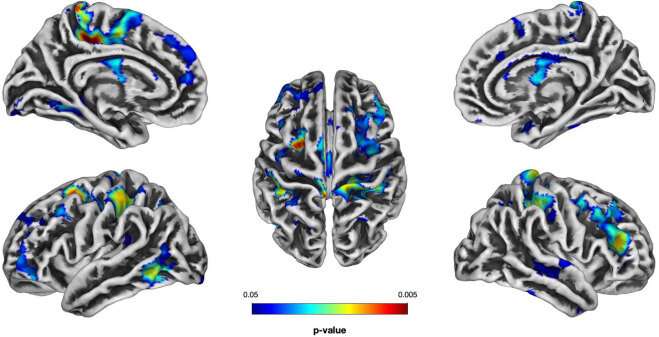

Brain scans of children ages 9–10 with a type of eating disorder that causes uncontrollable overeating showed differences in gray matter density compared to their unaffected peers, according to a USC-led study.

Binge eating disorder, which affects about 3–5% of the U.S. population, is characterized by frequent episodes of eating large amounts of food and a sense of having no control over the behavior. The study’s findings suggest that abnormal development in the brain’s centers for reward and inhibition may play a role.

The recently published study is available online in the journal Psychiatry Research.

“In children with binge eating disorder, we see abnormality in brain development in brain regions specifically linked to reward and impulsivity, or the ability to inhibit reward,” said lead author Stuart Murray, Della Martin Associate Professor of Psychiatry and the Behavioral Sciences at the Keck School of Medicine of USC, where he serves as director of the Eating Disorders Program.

“These kids have a very, very heightened reward sensitivity, especially toward calorically dense, high-sugar foods. The findings underscore the fact that this is not a lack of discipline for these kids.”

Pandemic saw increase in eating disorders among young people

Experts say eating disorders in young people soared during the pandemic, along with steep increases in hospitalizations. Social isolation, stress, disruption of routine and a social media-fueled quest for perfection all exacerbated disorders such as anorexia, muscle dysmorphia and binge eating.

Binge eating disorder puts people at risk for obesity, metabolic syndrome, abnormal cardiac function and suicidal thoughts. Treatment goals include reducing the frequency of binge eating episodes by removing “trigger” foods, as well as addressing underlying anxiety or depression. Treatment with medication and talk therapy is effective about only half the time, Murray said.

For this study, Murray and his colleagues analyzed brain scans and other data from 71 children with diagnosed binge eating disorder and 74 children without binge eating disorder, who are part of a large longitudinal study called the Adolescent Brain and Cognitive Development Study. That study includes data of 11,875 children ages 9–10 who were enrolled in 2016–2018 and recruited from 21 sites around the U.S.

In the children with binge eating disorder, they saw elevations in gray matter density in areas that are typically “pruned” during healthy brain development. Synaptic pruning, a development phase that occurs between ages two and 10, eliminates synapses that are no longer used, making the brain more efficient. Disturbed synaptic pruning is linked to a number of psychiatric disorders.

“This study suggests to me that binge eating disorder is wired in the brain, even from a very, very early age,” Murray said. “The question that we don’t know, which is something that we will address in time, is whether successful treatment of binge eating disorder in kids helps correct brain development. The prognosis of almost all psychiatric diseases is better if you can treat them in childhood.”

Leigh Hopper, University of Southern California