The death rate for people who have a tear in a major artery coming out of the heart—aortic dissection—has been rising over the past decade, especially among women and Black adults, new research shows.

And while death rates for women increased faster, older men continued to face an overall greater risk of dying from this uncommon but often fatal tear in the main artery carrying blood from the heart to the rest of the body. The findings were published Friday in the Journal of the American Heart Association.

The increasing death rate suggests “we have more room to improve in the prevention and management of aortic dissections,” said lead author Dr. Salik Nazir, a cardiology fellow at the University of Toledo Medical Center and ProMedica Toledo Hospital in Ohio.

“One would expect decreasing mortality over time as seen with many other cardiovascular diseases,” Nazir said. But “risk factors such as uncontrolled hypertension, obesity, smoking, diabetes and older age have been increasing within the United States, plausibly explaining our important findings.”

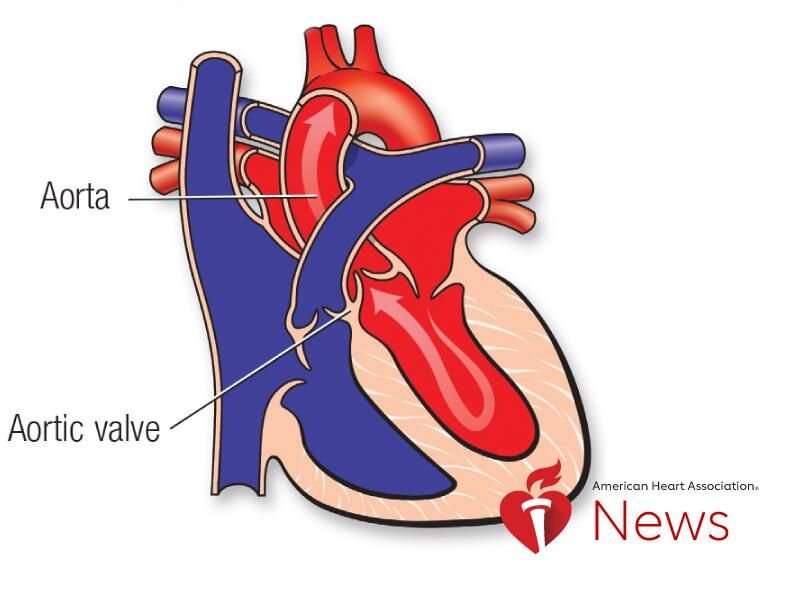

Aortic dissection, also known as AoD, occurs when blood pumping through the aorta splits the layers of the artery wall, trapping blood coming from the heart. The pressure from the pooled, leaking blood can cause a rupture and decreased blood flow to other organs.

Surgery can repair the damaged artery section or medication can lower blood pressure and reduce the risk of rupture.

This study analyzed overall AoD death rates in the U.S. from 1999 to 2019 , using data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and a national death certificate database. Researchers found rates initially fell 1.5% each year from 1999 to 2012, before reversing course and climbing an average 2.5% per year from 2012 to 2019.

The results, Nazir said, point to the need for improvements in prevention, especially among groups disproportionately affected

Black adults experienced a higher annual increase of AoD deaths, 4% per year from 2012 to 2019, as well as the highest rates throughout the study period—from 28.7 deaths per million in 1999 to 35.7 per million in 2019.

The initial decrease in overall AoD death rates and the subsequent reversal mirrors trends in high blood pressure rates, which fell by 2013-2014 and then climbed by 2017-2018, according to the CDC. But Black adults—who have substantially higher rates of hypertension, a major risk factor for AoD—did not experience the same decline, Nazir said, which could explain the disproportionate effect in AoD death rates for this group.

Black people also are disproportionately affected by negative social determinants of health, such as structural racism , he said. “Furthermore, residents of medically underserved areas have unequal access to health care resources to control their blood pressure, diabetes or other potential risk factors for AoD.”

Both women and men saw an initial decline in death rates followed by an increase from 2012 to 2019, but that annual increase was higher among women (3.1% per year) than men (2.6% per year).

AoD is hard to diagnose and may often be missed in women, who are more likely to have atypical symptoms than men, Nazir said. For example, women may experience shortness of breath, rather than chest pain, which is more typical. Symptoms also can include a sudden stabbing pain in the neck, jaw, abdomen, chest or shoulder, fainting, difficulty breathing or sudden weakness.

There are two types of AoD, classified by whether the damage involves the ascending portion of the aorta—Type A—or the descending portion, called Type B. Both types can be fatal, but people hospitalized for Type A dissections experience higher death rates than those hospitalized for Type B.

Dr. Bo Yang, an associate professor in the department of cardiac surgery at the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, said the study did not differentiate between Type A or B, nor whether it was acute or chronic in severity. “This makes it challenging to interpret the results,” said Yang, who was not involved in the research.

Yang was a co-investigator on a 2021 study that found higher death rates for men than women from surgery to repair acute Type A, which he believes is related to women managing their overall health and risk factors better than men.

“When patients come to us, the women are older than the men but otherwise most are pretty healthy,” he said. “You repair the aorta, and they survive the operation.”

He said further research is needed to explain the differing trends seen between men and women in this study.

Laura Williamson