When a baby or toddler dies without warning, parents often blame themselves. A study at Boston Children’s may provide some insight into sudden, unexplained child deaths and perhaps a measure of closure. It suggests that at least 10% of children who die suddenly have an undiagnosed genetic condition that caused or contributed to their death.

“When we first meet with families, they may say, “Well, they told me it was SIDS, and it meant they don’t know anything and there’s nothing to do,'” says Dr. Richard Goldstein, who directs Robert’s Program on Sudden Unexpected Death in Pediatrics. “That’s not really fair and it’s not enough. There is plenty we can do.”

In the study, published in the journal Genetics in Medicine, Dr. Goldstein and his colleagues took a deep dive into the cases of 352 children who died suddenly without explanation. Most cases were classified as sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS), occurring before 12 months of age, but some children were three years or older. (Dr. Goldstein and others now use the umbrella term “sudden unexpected death in pediatrics” to include deaths that occur after infancy.)

The researchers sequenced DNA from each child, initially looking at a panel of genes that Robert’s Program has developed. They also consulted autopsy reports, medical records, and information on the family’s medical history. Experts in pediatrics, genetics, metabolism, neurology, cardiac genetics, pathology, and neuropathology reviewed each case.

Exploring unexpected child deaths

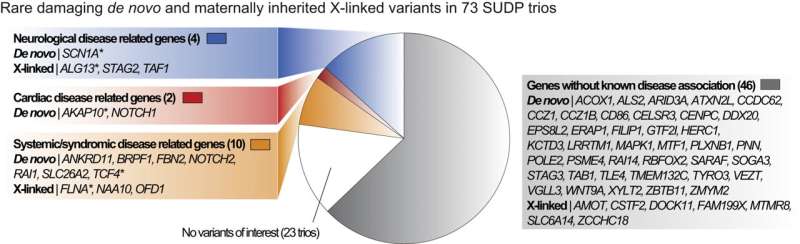

While some deceased children had known risk factors for sudden unexpected death, such as sleeping in cribs with soft bedding, 37 children (11%) had genetic changes, known as variants, that likely played a role in their deaths. Many of these variants were in genes related to heart conditions, metabolic disorders, neurologic disorders such as epilepsy, or genetic syndromes affecting multiple systems in the body.

“In two children, we found a variant in a gene linked to a genetic syndrome that explained the child’s characteristics, but without a diagnosis being made prior to death,” says Dr. Ingrid Holm, a study co-investigator whose research at Boston Children’s focuses on the ethical, legal, and social implications of genomics research. “These syndromes had not been associated with sudden death before.”

The team also compared some of the children’s genomes with those of their parents. In some cases, this led them to identify variants in the child that they did not find in either parent (so-called de novo variants). In other cases, the mother or father did carry the same variant, but seemed not to be affected.

Overlooked genetic conditions

The research also revealed early hints of problems in some children that had been overlooked. For example, some children with variants in epilepsy-related genes had previously experienced seizures during a fever episode. Since febrile seizures are common in young children, these by themselves would not have raised a red flag. Other children turned out to have family members with heart disease or neurologic disorders, or showed subtle facial or behavioral signs of an underlying disorder.

“As with other unexplained conditions in children, we have shown that the otherwise unexplained death of an infant or child deserves an exhaustive look for underlying genetic causes,” says Dr. Annapurna Poduri, another co-investigator on the study who directs the Epilepsy Genetics Program at Boston Children’s. “I sincerely hope our research makes this approach the rule rather than the exception.”

A path forward for grieving families

Robert’s Program offers bereaved parents an opportunity to understand why their child died. Often, the process of genetic testing, gathering information about the child’s and family’s medical history, and engaging other family members helps parents adapt to their loss. In some cases, based on these investigations, counselors can reassure families that their child most likely died peacefully.

“We’re not at the point where we can actually explain everything, but we can tell families that we’ve looked as hard as possible,” Dr. Goldstein says. “Our work provides strong evidence that it’s worthwhile to do genetic testing.”

Nancy Fliesler, Children’s Hospital Boston