In a study published today in Blood Advances, researchers found that privately insured individuals with sickle cell disease (SCD) spend approximately $1.7 million on disease-related medical expenses over their lifetime. These findings highlight the enormous economic burden affecting individuals living with SCD and raise questions about how medical advancements, like gene therapy, may one day factor into the cost of care.

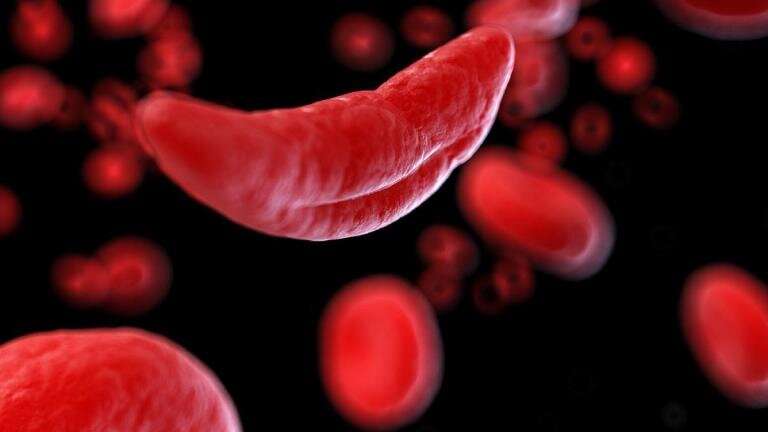

SCD is the most common inherited red blood cell disorder in the United States, affecting an estimated 100,000 people. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), SCD affects one out of every 365 Black or African American births and one out of every 16,300 Hispanic American births. Considering that SCD disproportionately affects Black and Hispanic communities, such high health care costs put even further inordinate financial constraints on these populations.

This research, funded by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, Cure Sickle Cell Initiative, not only brought the exorbitant total medical costs attributable to SCD to light but also uncovered that people with SCD pay significant out-of-pocket costs on private insurance plans.

“Our findings suggest that the lifetime out-of-pocket cost of medical care is about $44,000 for people with SCD,” explained study author Kate Johnson, Ph.D., of the Comparative Health Outcomes, Policy & Economics (CHOICE) Institute, Department of Pharmacy, University of Washington. “For this population, the annual out of pocket cost burden could be five to 10% of their annual income.”

To conduct this study, Dr. Johnson and colleagues collected data from a retrospective cohort of individuals between birth and age 64 diagnosed with SCD from 2007 to 2018 through a commercial claims database. The repository contained information such as outpatient and inpatient medical claims, prescription drug claims, health utilization records, payer and individual costs, demographics, and insurance plans. They then analyzed these statistics against matched controls without SCD.

Results revealed that non-elderly lifetime SCD-related medical expenses add up to approximately $1.6 million for women and $1.7 million for men. Notably, participants also spent around $44,000 on out-of-pocket expenses. Additionally, these results suggested that the medical costs of treating SCD peaked around the age of 13-24 years old and declined with older age. The researchers believe this could be attributed both to the typical progression of SCD and to adolescence and young adulthood being a transitional period of life, when their care delivery may be changing or they may be switching insurance plans.

Dr. Johnson noted that this study is limited in that these findings do not encompass the indirect costs one can accumulate when receiving care for SCD, such as lost productivity due to being unable to work or time spent managing the disease, both for patients and their caregivers. She also emphasized that the figures do not include people covered on public insurance plans, like Medicaid, and that only a third of patients with SCD have private insurance.

In the long term, the teams at the University of Washington and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, tasked to lead the Cure Sickle Cell Economic Impact Consortium, aim to lay out a comprehensive picture of the total cost of living with SCD. They believe it is imperative to assess the costs of treatments for SCD, like gene therapy, and evaluate how these innovations can reduce the financial strain of living with this disease.

“Hopefully, these findings will trigger some conversation around the pricing of gene therapies,” said Dr. Johnson. “While SCD is a rare disease, the current treatments available are placing a substantial economic burden on individuals and our entire health care system.”

American Society of Hematology