Infantile spasm (IS) is a severe epileptic syndrome of infancy and accounts for 50% of all epilepsy cases that occur in babies during the first year of life. Current treatment options for this disorder are limited and most affected infants grow up to have developmental delays, intellectual disabilities and other types of severe epilepsy. A groundbreaking study, conducted in the laboratory of Dr. John Swann, director of the Gordon and Mary Cain Pediatric Neurology Research Foundation labs, investigator at the Jan and Dan Duncan Neurological Research Institute at Texas Children’s Hospital and professor at Baylor College of Medicine, has found that the levels of insulin growth factor -1 (IGF-1) and its downstream signaling are reduced in the brains of both IS patients and animal models. Furthermore, they found that the administration of an IGF-1 analog to an IS animal model successfully eliminated spasms and abnormal brain activity. This exciting study, published in the Annals of Neurology, has the potential to transform the treatment landscape for babies with infantile spasms.

Dr. Swann is a leading expert in epilepsy research and a few years back, his team’s pioneering discoveries resulted in an FDA-approved treatment for severe epilepsy among tuberous sclerosis patients. He and his team have had a longstanding interest and experience in studying infantile spasms, an epileptic disorder diagnosed in roughly 2500 babies in the United States each year.

Early-life brain injuries reduce IGF-1 levels and impair the IGF-1 signaling pathway

“It has been previously reported that IS patients with preexisting brain abnormalities have low levels of IGF-1 in their cerebrospinal fluid and based on that study, we were interested in investigating if IGF-1 levels were altered in the brains of IS animals and patients,” Swann said.

For their investigations, the team used a well-established method to induce spontaneous epileptic spasms in rodents. This methodology, developed in 2008 in the Swann lab, involves chronic infusion of tetrodotoxin (TTX) into the cortex of the infant rat brain, which causes injury at the infusion site and results in spasms that are virtually identical to the those seen in IS patients.

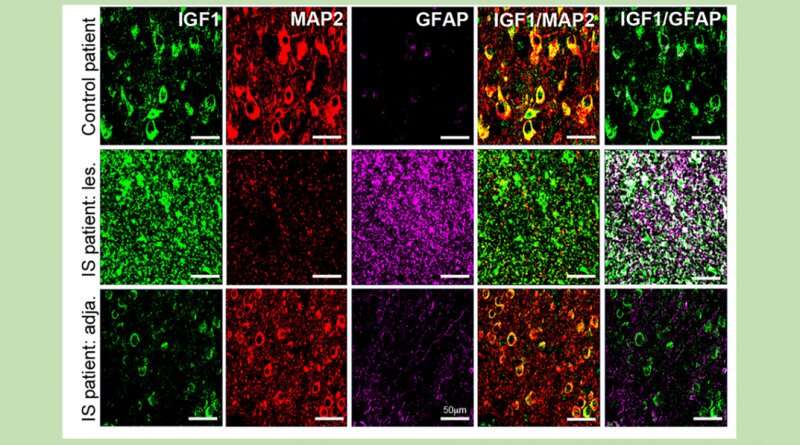

“As is expected after a brain injury, we saw an increase in IGF-1 levels in the non-neuronal support cells (aka glia) at the site of TTX infusion. However, we were most intrigued by the remarkable and widespread decrease in IGF-1 expression in cortical neurons in brain regions adjacent to or further away from the site of TTX injection—a phenomenon that had never been reported before,” Swann said.

Next, the team studied resected cortical tissue from IS patients who had prior perinatal strokes and had undergone surgery to control their intractable seizures. The results were remarkably similar to what they had seen in IS animals.

“More importantly, we found this reduction in cortical levels of IGF-1 had significant consequences in IS animal models because it dampened the overall activity of the IGF-1 molecular signaling pathways that regulate many important biological processes involved in early brain development and neuronal function,” said Dr. Carlos Ballester-Rosado, a postdoctoral associate in the Swann lab and first author of the study.

An IGF-1 analog eliminates infantile spasms in animals

To determine if increasing IGF-1 levels in the cortex of IS animals could ameliorate spasms, the team used a smaller version of IGF-1 that can cross the blood-brain barrier with greater ease than the full-length hormone. The IGF-1 tripeptide they tested is a natural by-product of IGF-1 breakdown that is found normally in the brain. Moreover, this analog has been previously demonstrated to successfully reverse behavioral defects in animal models of other neurodevelopmental disorders such as Rett syndrome and Phelan-McDermid syndrome.

“Using several lines of evidence, we first confirmed that this IGF-1 tripeptide was capable of activating the IGF-1 signaling cascade in mice,” Swann said. “We then found — to our astonishment — that administration of IGF-1 successfully eliminated spasms and an IS-specific chaotic brain activity pattern called hypsarrhythmia in most of the IS animals. We are excited because these findings raise the tantalizing possibility that this IGF-1 analog can be used to treat IS patients in the future.

Texas Children’s Hospital