The world has changed since 1664, when French philosopher and scientist Rene Descartes first claimed the brain was responsible for feeling the sensation of pain.

However, a key question remains: How exactly does the human brain feel pain? Specifically, thermal pain—like that experienced when touching an open flame or a hot pan while cooking.

A team of researchers in the neurosciences department at the Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine think they’ve found an answer—that a neural circuit involving spinal neurons and a signaling pathway––are responsible for how burning pain is sensed.

They believe their discovery, published recently in the journal Neuron, could lead to more effective treatment for chronic, pathological pain—such as shooting, stabbing and burning pain—because it may involve the same signaling pathway.

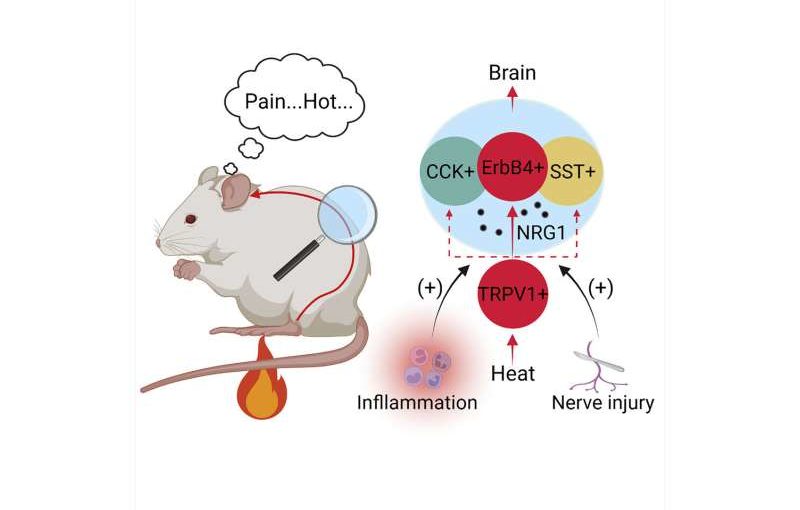

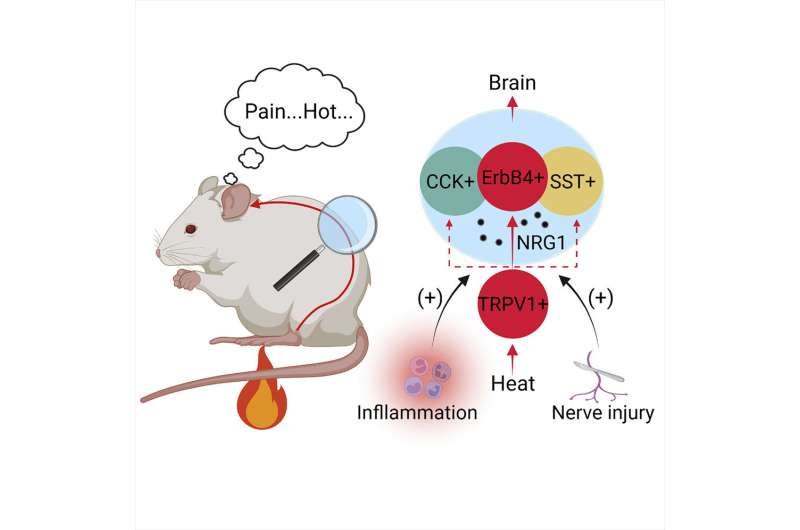

“We know that heat, cold, pressure and itching stimulations to our skin result in appropriate feelings in the brain. However, the neurons encoding the heat signals in the spinal cord were unclear,” said Hongsheng Wang, study lead author and a postdoctoral fellow at the School of Medicine. “Our study identified a group of interneurons in the spinal cord required for heat sensation. We also found a signaling pathway contributes to heat hypersensitivity caused by inflammation or nerve injuries.”

The study

The brain controls everything we do, from our perception of the world around us to how we move our bodies and experience sensations. The process involves neurons, which are cells that act as messengers to transmit information between the brain and nervous system. The neurons send information through complex circuits throughout the body.

The research team looked at neurons in the spinal cord and their role in thermal pain by analyzing mouse models and their response to heated plates. During this process, the team identified the activation of a “novel,” or newly discovered, class of spinal cord neurons (called ErbB4+) that process heat signals to the spinal cord.

The team wanted to look further into whether these neurons specifically are responsible for thermal pain. There are several ways to test this, including destroying the ErbB4+ neurons.

The researchers expressed a toxin specifically targeting the ErbB4+ neurons. Once the neurons were destroyed, the response to heat pain was impaired. This demonstrated that ErbB4+ neurons are specifically tied to how thermal pain is sensed and, when destroyed, pain is not felt less.

They also examined the role of neuregulin 1 (NRG1), a protein involved in many cellular functions. They found that NRG1 and its receptor tyrosine kinase ErbB4 (often referred to as the NRG1 signaling) is also involved in the sensation of thermal pain.

The findings

“Pain is a sensation we have all experienced. For most of us, pain is temporary,” said Lin Mei, professor and chair of the Department of Neurosciences at the School of Medicine and study corresponding author. “However, for patients with pathological pain, the pain experience is unending, with little hope for relief. Scientists have long believed it’s a result of dysfunctional neuronal activity.”

Mei said their study showed that pathological pain can be reduced by injecting an ErbB4+ inhibitor or an NRG1 neutralizing peptide.

The application of these discoveries may go beyond the therapeutic treatment of pathological pain.

“Both NRG1 and ErbB4 are risk genes of many brain disorders including major depression and schizophrenia,” Mei said. “Further studies are warranted to show if the mechanism of heat pain and pathological pain also plays a role in different types of pain experienced by those who have brain disorders.”

Case Western Reserve University