Approximately 1 in 25 people will develop colon cancer during their lifetime and nearly 2 million cases new cases are diagnosed worldwide each year. Chemotherapy is commonly used to treat colon cancer. While this treatment is initially effective in most cases, many patients relapse after treatment.

Led by Dr. Eduard Batlle, ICREA researcher and head of the Colorectal Cancer Laboratory at IRB Barcelona, this study reveals that some tumor cells remain in a latent state and, after chemotherapy, they are reactivated, thus causing relapse. Their study is published in Nature Cancer.

In short, scientists have discovered that tumor stem cells with Mex3a protein activity remain in a state of latency that confers resistance to chemotherapy. Due to the action of the drugs used in this treatment, these cells adopt a state similar to the embryonic one, and sometime after chemotherapy, when the environment is more favorable, they are reactivated to regenerate the tumor in all its complexity. These persistent cells are responsible for cancer relapse after treatment.

“Chemotherapy is effective and kills most of the tumor cells but not all of them. Our discovery reveals the identity of a group of persistent cells that are resistant to chemotherapy go on to regenerate the tumor after treatment. Our work paves the way for the development of drugs to eliminate these cells, which would make chemotherapy more effective and improve survival rates,” explains Dr. Batlle, also a group leader in the Cancer CIBER (CIBERONC).

Organoids, analysis of samples from patients, and the Mex3a gene

This study has been carried out using mainly organoids, which are samples of tumors from patients (or from mouse models of advanced cancer) that can be grown in the laboratory and that reproduce the complexity of the tumor in terms of its three-dimensional structure and variability of cell types. “The organoids have allowed us to trace the evolution of the cells responsible throughout the process and observe their reaction to chemotherapy,” explains Adrián Álvarez-Varela, the first author of the study.

The study also involved the use of mouse models of colorectal cancer, in which the researchers were able to observe and reproduce the behavior of these persistent cells, as in the organoids. Finally, the results obtained in organoids and mice were contrasted with the transcriptomic analysis of samples from patients.

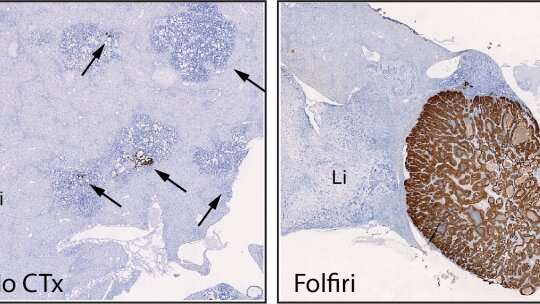

In addition, Dr. Batlle and collaborators show that removal of the Mex3a gene by means of genetic engineering techniques makes colorectal cancer cells highly sensitive to chemotherapy. In experimental models of this type of cancer, metastases that are deficient in Mex3a are completely eliminated with chemotherapy. Although the functions of the Mex3a gene are still unknown, this finding suggests that drugs targeting it could act synergistically with chemotherapy and prevent relapse.

Future laboratory work will focus on analyzing the underlying molecular mechanisms, in particular how the Mex3a protein maintains cancer stem cells in this dormant state. It will also address the processes triggered by chemotherapy that allow the cells to generate a state similar to the embryonic one, which gives them the potential to regenerate the different cell types present in the tumor when treatment has ended.

University of Barcelona