Screening sperm may help identify potentially harmful new genetic mutations and help fertility specialists prevent them from being passed on to offspring, shows a preliminary study published in eLife.

The results suggest a potential tool to help improve fertility treatment outcomes.

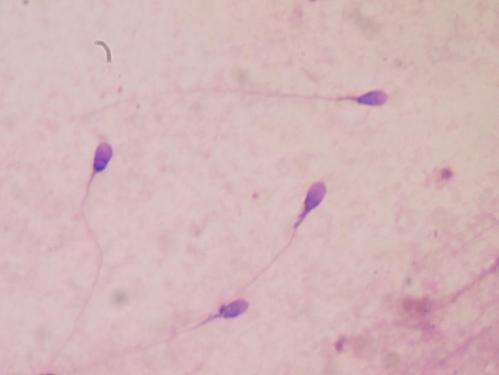

New harmful disease-causing mutations can arise in sperm, and fathers may inadvertently pass them along to their offspring during fertilization. These mutations may cause miscarriages or lead to a child developing a congenital disease that neither parent has.

“Every male harbors up to dozens of these new mutations in their sperm, some of which are potentially harmful,” says co-senior author Martin Breuss, Assistant Professor in the clinical genetics and metabolism section of the Department of Pediatrics, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Colorado, US. “But whether testing sperm for such mutations could help predict or prevent the risk of transmission to their children is unclear.”

Three couples undergoing in-vitro fertilization treatments agreed to participate in the research. The investigators used whole-genome sequencing to detect new mutations in sperm samples from each man. They then tested preimplantation embryos at a very early stage of development from each couple for these mutations.

The team identified 55 mutations in the men’s sperm, including 15 passed on to an embryo. In some cases, more than one of a couple’s embryos had one of the mutations resulting in 19 cases of transmission. Mutations were passed on to the embryos slightly less often than the authors anticipated.

“Our results confirm that new mutations in sperm can be transmitted to embryos,” says co-lead author Xiaoxu Yang, a postdoctoral scholar at the University of California, San Diego, US. “Preimplantation genetic testing of embryos could be used to select embryos that did not receive one of the harmful new mutations detected in their father’s sperm.”

Previous studies by this team suggested that one in 300 children conceived through in-vitro fertilization have a poor pregnancy outcome or poor health caused by a new mutation in their father’s sperm.

“If larger studies confirm our findings, this new approach could result in more positive outcomes for families struggling with infertility by helping prevent pregnancy loss or congenital diseases,” concludes senior author Joseph Gleeson, Director of Neurodevelopmental Genetics and endowed chair of Rady Children’s Institute for Genomic Medicine in San Diego, California, US.

eLife