Parkinson’s is a progressive and debilitating disease of the brain that eventually compromises patients’ ability to walk and even to talk. Its diagnosis is complex, and in the early stages—impossible.

The usual method of visualizing brain structure utilizes a technique most of us are familiar with, called MRI. However, it is not sensitive enough to reveal the biological changes that take place in the brain of Parkinson patients, and at present is primarily only used to eliminate other possible diagnoses.

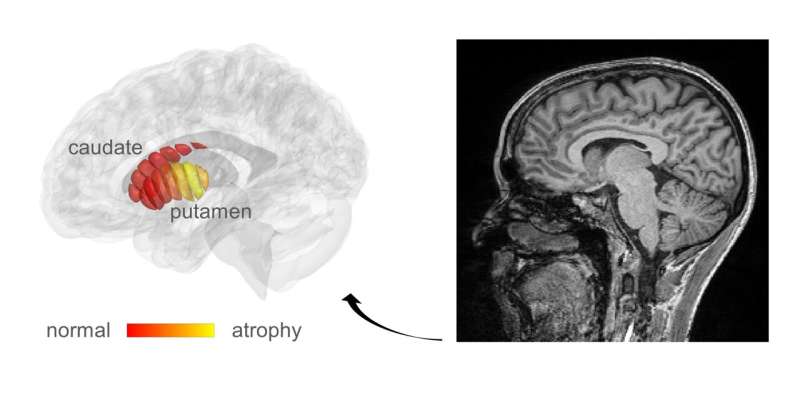

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HU) researchers, led by Professor Aviv Mezer, realized that the cellular changes in Parkinson’s could possibly be revealed by adapting a related technique, known as quantitative MRI (qMRI). Their method has enabled them to look at microstructures within the part of the deep brain known as the striatum—an organ which is known to deteriorate during the progress of Parkinson’s disease. Using a novel method of analysis, developed by Mezer’s doctoral student, Elior Drori, biological changes in the cellar tissue of the striatum were clearly revealed. Moreover, they were able to demonstrate that these changes were associated with the early stages of Parkinson’s and patients’ movement dysfunction. Their findings were published today in the journal Science Advances.

qMRI achieves its sensitivity by taking several MRI images using different excitation energies—rather like taking the same photograph in different colors of lighting. The HU researchers were able to use their qMRI analysis to reveal changes in the tissue structure within distinct regions of the striatum. The structural sensitivity of these measurements could only have been previously achieved in laboratories examining the brain cells of patients post mortem, which is not an ideal situation for detecting early disease or monitoring the efficacy of a drug.

“When you don’t have measurements, you don’t know what is normal and what is abnormal brain structure, and what is changing during the progress of the disease,” explained Mezer. The new information will facilitate early diagnosis of the disease and provide “markers” for monitoring the efficacy of future drug therapies. “What we have discovered,” he continued “is the tip of the iceberg.” It is a technique that they will now extend to investigate microstructural changes in other regions of the brain. Furthermore, the team are now developing qMRI into a tool that can be used in a clinical setting. Mezer anticipates that is about 3–5 years down the line.

Drori further suggests that this type of analysis will enable identification of subgroups within the population suffering from Parkinson’s disease—some of whom may respond differently to some drugs than others. Ultimately, he sees this analysis “leading to personalized treatment, allowing future discoveries of drug with each person receiving the most appropriate drug.”

Hebrew University of Jerusalem