The spread of monkeypox in the U.S. could represent the dawn of a new sexually transmitted disease, though some health officials say the virus that causes pimple-like bumps might yet be contained before it gets firmly established.

Experts don’t agree on the likely path of the disease, with some fearing that it is becoming so widespread that it is on the verge of becoming an entrenched STD—like gonorrhea, herpes and HIV.

But no one’s really sure, and some say testing and vaccines can still stop the outbreak from taking root.

So far, more than 2,400 U.S. cases have been reported as part of an international outbreak that emerged two months ago.

Health officials are not sure how fast the virus has spread. They have only limited information about people who have been diagnosed, and they don’t know how many infected people might be spreading it unknowingly.

They also don’t know how well vaccines and treatments are working. One impediment: Federal health officials do not have the authority to collect and connect data on who has been infected and who has been vaccinated.

With such huge question marks, predictions about how big the U.S. outbreak will get this summer vary widely, from 13,000 to perhaps more than 10 times that number.

Dr. Rochelle Walensky, director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said the government’s response is growing stronger every day and vaccine supplies will soon surge.

“I think we still have an opportunity to contain this,” Walensky told The Associated Press.

Monkeypox is endemic in parts of Africa, where people have been infected through bites from rodents or small animals. It does not usually spread easily among people.

But this year more than 15,000 cases have been reported in countries that historically don’t see the disease. In the U.S. and Europe, the vast majority of infections have happened in men who have sex with men, though health officials have stressed that anyone can catch the virus.

It spreads mainly through skin-to-skin contact, but it can also be transmitted through linens used by someone with monkeypox. Although it’s been moving through the population like a sexually transmitted disease, officials have been watching for other types of spread that could expand the outbreak.

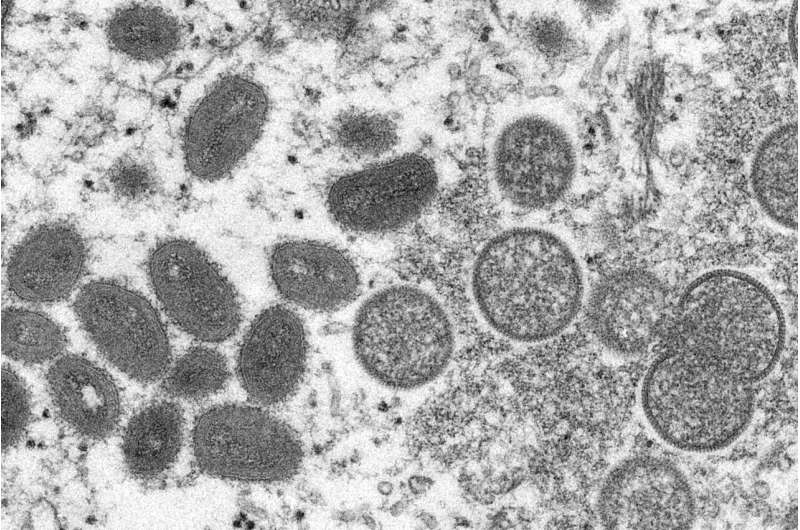

Symptoms include fever, body aches, chills, fatigue and the bumps on parts of the body. The illness has been relatively mild in many men, and no one has died in the U.S. But people can be contagious for weeks, and the lesions can be extremely painful.

When monkeypox emerged, there was reason to believe that public health officials could control it.

The tell-tale bumps should have made infections easy to identify. And because the virus spreads through close personal contact, officials thought they could reliably trace its spread by interviewing infected people and asking who they had been intimate with.

It didn’t turn out to be that easy.

With monkeypox so rare in the U.S., many infected men—and their doctors—may have attributed their rashes to some other cause.

Contact tracing was often stymied by infected men who said they did not know the names of all the people they had sex with. Some reported having multiple sexual interactions with strangers.

It didn’t help that local health departments, already burdened with COVID-19 and scores of other diseases, now had to find the resources to do intensive contact-tracing work on monkeypox, too.

Indeed, some local health officials have given up expecting much from contact tracing.

There was another reason to be optimistic: The U.S. government already had a vaccine. The two-dose regimen called Jynneos was licensed in the U.S. in 2019 and recommended last year as a tool against monkeypox.

When the outbreak was first identified in May, U.S. officials had only about 2,000 doses available. The government distributed them but limited the shots to people who were identified through public health investigations as being recently exposed to the virus.

Late last month, as more doses became available, the CDC began recommending that shots be offered to those who realize on their own that they could have been infected.

Demand has exceeded supply, with clinics in some cities rapidly running out of vaccine doses and health officials across the country saying said they don’t have enough.

That’s changing, Walensky said. As of this week, the government has distributed more than 191,000 doses, and it has 160,000 more ready to send. As many as 780,000 doses will become available as early as next week.

Once current demand is satisfied, the government will look at expanding vaccination efforts.

The CDC believes that 1.5 million U.S. men are considered at high risk for the infection.

Testing has also expanded. More than 70,000 people can be tested each week, far more than current demand, Walensky said. The government has also embarked on a campaign to educate doctors and gay and bisexual men about the disease, she added.

Donal Bisanzio, a researcher at RTI International, believes U.S. health officials will be able to contain the outbreak before it becomes endemic.

But he also said that won’t be the end of it. New bursts of cases will probably emerge as Americans become infected by people in other countries where monkeypox keeps circulating.

Walensky agrees that such a scenario is likely. “If it’s not contained all over the world, we are always at risk of having flare-ups” from travelers, she said.

Shawn Kiernan, of the Fairfax County Health Department in Virginia, said there is reason to be tentatively optimistic because so far the outbreak is concentrated in one group of people—men who have sex with men.

Spread of the virus into heterosexual people would be a “tipping point” that may occur before it’s widely recognized, said Kiernan, chief of the department’s communicable disease section.

Spillover into heterosexuals is just a matter of time, said Dr. Edward Hook III, emeritus professor of infectious diseases at the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

If monkeypox becomes an endemic sexually transmitted disease, it will be yet another challenge for health departments and doctors already struggling to keep up with existing STDs.

Such work has long been underfunded and understaffed, and a lot of it was simply put on hold during the pandemic. Kiernan said HIV and syphilis were prioritized, but work on common infections like chlamydia and gonorrhea amounted to “counting cases and that’s about it.”

For years, gonorrhea, chlamydia and syphilis cases have been rising.

“By and large,” Hook said, doctors “do a crummy job of taking sexual histories, of inquiring about and acknowledging their patients are sexual beings.”

MIKE STOBBE