Elementary school-age children who get less than nine hours of sleep per night have significant differences in certain brain regions responsible for memory, intelligence and well-being compared to those who get the recommended nine to 12 hours of sleep per night, according to a new study led by University of Maryland School of Medicine (UMSOM) researchers. Such differences correlated with greater mental health problems, like depression, anxiety, and impulsive behaviors, in those who lacked sleep. Inadequate sleep was also linked to cognitive difficulties with memory, problem solving and decision making. The findings were published today in the journal The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health.

The American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommends that children aged six to 12 years of age sleep 9 to 12 hours per night on a regular basis to promote optimal health. Up until now, no studies have examined the long-lasting impact of insufficient sleep on the neurocognitive development of pre-teens.

To conduct the study, the researchers examined data that were collected from more than 8,300 children aged nine to 10 years who were enrolled in the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development (ABCD) study. They examined MRI images, medical records, and surveys completed by the participants and their parents at the time of enrollment and at a two-year follow-up visit at 11 to 12 years of age. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the ABCD study is the largest long-term study of brain development and child health in the U.S.

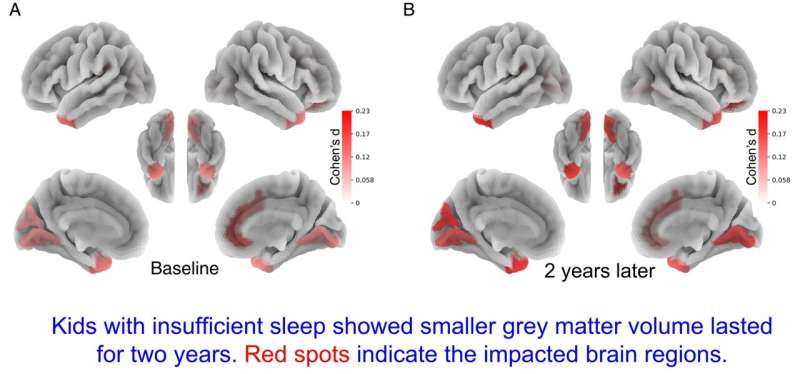

“We found that children who had insufficient sleep, less than nine hours per night, at the beginning of the study had less gray matter or smaller volume in certain areas of the brain responsible for attention, memory and inhibition control compared to those with healthy sleep habits,” said study corresponding author Ze Wang, Ph.D., Professor of Diagnostic Radiology and Nuclear Medicine at UMSOM. “These differences persisted after two years, a concerning finding that suggests long term harm for those who do not get enough sleep.”

This is one of the first findings to demonstrate the potential long-term impact of lack of sleep on neurocognitive development in children. It also provides substantial support for the current sleep recommendations in children, according to Dr. Wang and his colleagues.

In follow-up assessments, the research team found that participants in the sufficient sleep group tended to gradually sleep less over two years, which is normal as children move into their teen years, whereas sleep patterns of participants in the insufficient sleep group did not change much. The researchers controlled for socioeconomic status, gender, puberty status and other factors that could impact how much a child sleeps and affect brain and cognition.

“We tried to match the two groups as closely as possible to help us more fully understand the long-term impact on too little sleep on the pre-adolescent brain,” Dr. Wang said. “Additional studies are needed to confirm our finding and to see whether any interventions can improve sleep habits and reverse the neurological deficits.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics encourages parents to promote good sleep habits in their children. Their tips include making sufficient sleep a family priority, sticking with a regular sleep routine, encouraging physical activity during the day, limiting screen time and eliminating screens completely an hour before bed.

Fan Nils Yang, Ph.D., a post-doctoral fellow in Dr. Wang’s laboratory is a study co-author. Weizhen Xie, Ph.D., a researcher at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, is also a study co-author. UMSOM faculty members Thomas Ernst, Ph.D., and Linda Chang, MD, MS, are co-principal investigators of the ABCD study at the Baltimore site but were not involved in the data analysis of this new study.

“This is a crucial study finding that points to the importance of doing long-term studies on the developing child’s brain,” said E. Albert Reece, MD, Ph.D., MBA. “Sleep can often be overlooked during busy childhood days filled with homework and extracurricular activities. Now we see how detrimental that can be to a child’s development.”

University of Maryland School of Medicine