In a small patch of skin no bigger than an inch, there are millions of cells all performing duties, like protecting us from bacteria and sensing temperature. A portion of them are melanocytes, a type of cell dedicated to producing melanin, the substance that gives color to our skin, eyes, and hair. If triggered by UV light from the sun, melanocytes can form moles, or beauty marks.

Though harmless, moles are extremely common; some keep growing and mutating until they turn into melanoma, the most deadly type of skin cancer. While melanoma accounts for only about 1% of all skin cancers, it causes the majority of skin cancer-related deaths, most commonly in people under the age of 30, especially women. Approximately 30% of melanomas begin in existing moles on the skin.

But why do some moles keep growing, while others don’t? And can the same molecular function that stops regular moles from proliferating be applied to cancerous cells? A Boston University–led team of researchers has some answers—and their findings could lead to new drug targets for the successful treatment of cancer.

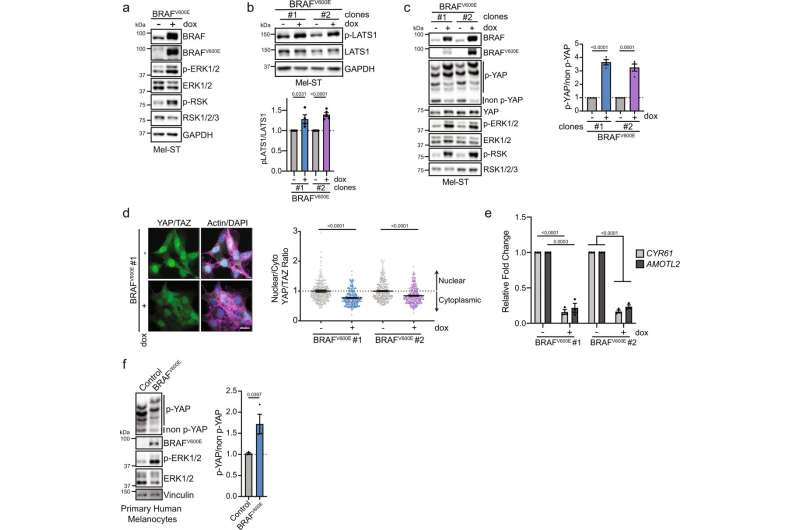

In a paper published in Nature Communications, they discovered that a signaling pathway that regulates growth in all cells—called the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway—plays a significant role in preventing the transformation of moles into melanoma. The pathway regulates growth by modulating two proteins in the cell. When active, these proteins change gene expression within cells to growth state. When inactivated, which happens when an organ reaches its full size, for example, the gene expression will change to stop growth in cells.

“The Hippo pathway can monitor how squished the cells are, which is basically how it knows that something is done growing,” says Neil J. Ganem, a corresponding author on the paper and a BU School of Medicine associate professor of pharmacology and medicine who studies differences between cancer cells and normal cells.

“We thought that’s what could be happening in these moles, and that the Hippo pathway stops the continuing growth of a mole,” Ganem adds. They looked at mice and human cells to see what happened when the Hippo pathway was turned on or off.

“When activated, we show the Hippo pathway restrains the growth of melanocytes and helps prevent their transformation into melanoma,” says Marc Vittoria, a fourth-year medical student at BU and lead author of the study. “Similarly, we found that when the Hippo tumor suppressor pathway is suppressed in melanocytes, those cells rapidly go on to form melanoma in multiple experimental models.”

The study was supported by a five-year grant from the Melanoma Research Alliance (MRA), called the Jackie King MRA Young Investigator Award, named after a 21-year-old who lost their life to melanoma. The MRA aims to bring young biologists with expertise in cancer cell biology into melanoma research.

“Melanoma is one of these cancers that can affect young people, making it particularly devastating,” Ganem says. “If you find it early, it’s easy to treat, but when you catch it late, and [it becomes] invasive, that is most difficult to treat.”

Doctors will often monitor moles that could be suspicious and opt to remove any that change over time. And discovering the mechanisms our cells employ to protect against tumor formation is key to identifying new drug targets for the successful treatment of cancer.

“We hope our study highlights that targeted reactivation of the Hippo pathway is an attractive therapeutic possibility for the future treatment of melanoma,” Ganem says. Though the research team focused on the role of the Hippo pathway in preventing moles from transforming into melanoma, they believe it may be acting similarly in other subtypes of cancer.

Boston University