In embryonic stages, tactile stimuli simultaneously activate tactile and visual neural pathways. Shortly after birth, both pathways reorganize to allow separate processing of touch and vision. Waves of activity emitted by the retina around birth drives the separation of touch and sight, according to a study by the UMH-CSIC Neurosciences Institute published today in Science. This separation occurs in a brain structure called the superior colliculus that acts as a distributor of neural circuits or pathways. Any delay in the development of this separation causes an incorrect organization of visual circuits that is maintained in adult life.

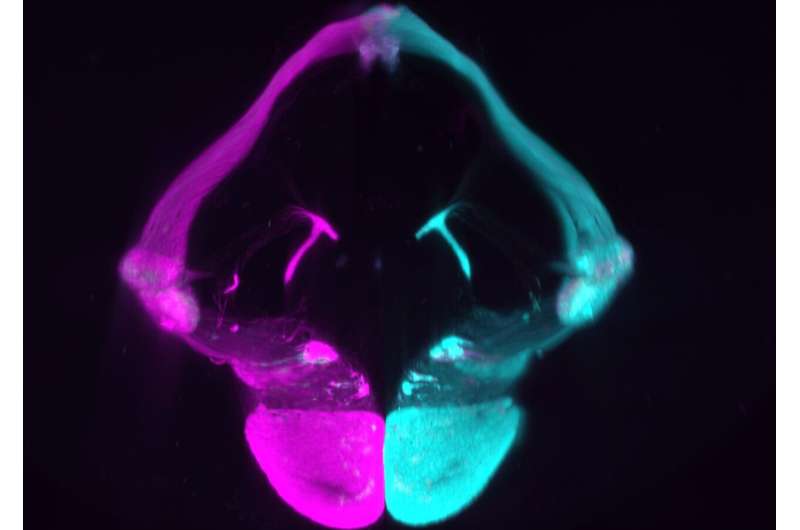

The new study from the laboratory of Dr. Guillermina López-Bendito, published today in Science, shows in mice that the circuits of touch and sight are not independent in the embryo, but are intermingled. It is at birth when these circuits separate and responses to sensory stimuli become independent.

In a previous study, López-Bendito’s lab showed that tactile stimuli activate brain circuits designed to process this type of information before birth. “But we wanted to determine whether they do so independently or whether there is a temporary overlap with other senses. This new study provides fascinating data on how the senses are segregated in the first days of life,” says Guillermina López-Bendito, who led the research.

In this work, led by Teresa Guillamón-Vivancos, they have shown, for the first time, in vivo in mice that during embryonic development a tactile stimulus not only triggers the expected response in the primary somatosensory cortex (one of the areas of the brain that deals with the sense of touch), but surprisingly also gives rise to a response in the primary visual cortex of both hemispheres.

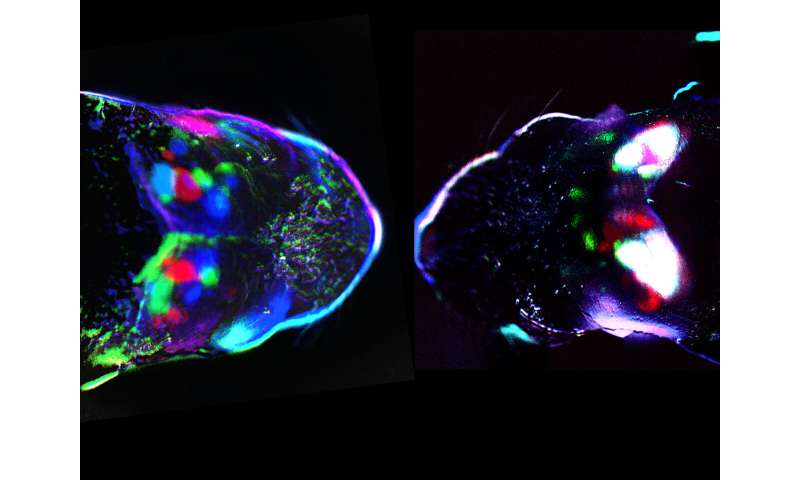

“This multimodal (i.e., encompassing more than one sense) response was observed in mouse embryos tested on the last day of gestation, but disappeared with birth. We then tested whether the disappearance of this multimodal response could be related to the arrival of signals from the retina to the cerebral cortex and other brain structures. Our data show that somatosensory and visual circuits are not secreted by default, but require the arrival of activity waves from the retina to do so,” explains Teresa Guillamón-Vivancos.

Pathway separation

This fundamental process of separation of sensory circuits occurs during a window of time close to birth, in a brain structure called the superior colliculus. Making a railway simile, at birth the senses separate in the superior colliculus, following different tracks. The change of pathway is facilitated by the activity waves of the retina, which act as switches that direct the stimuli of each sensory modality to the corresponding cortex, so that we can perceive them separately.

In fact, blocking these retinal waves prolongs the multimodal (intermixed) configuration of the senses after birth, resulting in superior colliculus retaining a mixed tactile-visual identity and defects in the spatial organization of the visual system arise.

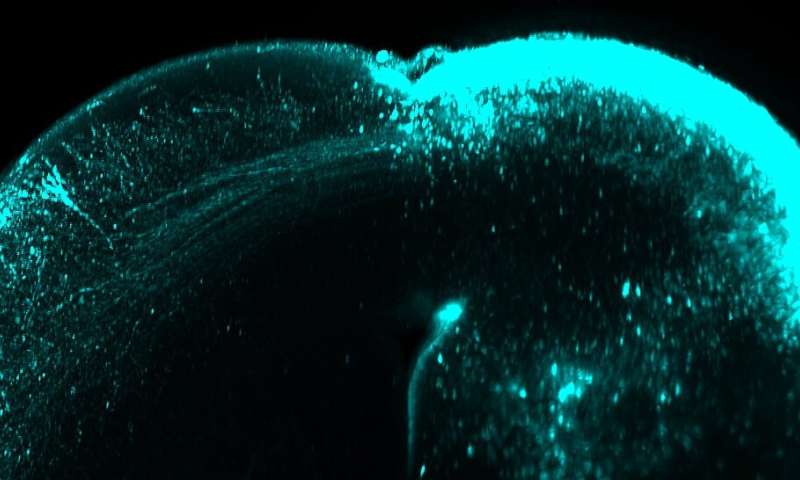

This work furthers the understanding of the function of retinal activity waves by revealing their decisive role in the acquisition of sensory modality specificity, expanding upon the classical role known in postnatal refinement of visual circuits.

Another important contribution of this work is the finding of a limited temporal window for the segregation of visual from somatosensory systems. Thus, any delay in this segregation will lead to long-lasting changes in the organization of visual circuits.

“Our results highlight the ontogenetic perspective, where the superior colliculus exerts master control during the early stages of organismal development over cortical specification and configuration of visual circuits. Therefore, we believe that a deeper understanding of the functional development of phylogenetically ancient structures is crucial to understand how the cerebral cortex forms and specifies its functional areas,” says Dr. López-Bendito.

Pilar Quijada, Spanish National Research Council (CSIC)