A large number of donated lungs cannot be used for transplantation. Researchers at Lund University in Sweden and Skåne University Hospital have conducted an animal study, bringing hope that more donor lungs could be used in the future. The researchers have launched a pilot study to investigate whether the treatment will have the same positive effects on human beings.

About 190 organs are donated in Sweden every year. Due to injuries to the lungs, only about 30% of them can be used for transplantation. Adding to that, the mortality rate is high: about half of the patients pass away within five years of transplant.

“The results from our study indicate that a certain treatment can help us use a larger part of a donor lung, and that there is an improved outcome during the first two days after surgery,” says Sandra Lindstedt, senior consultant in thoracic surgery at Skåne University Hospital and adjunct professor at Lund University.

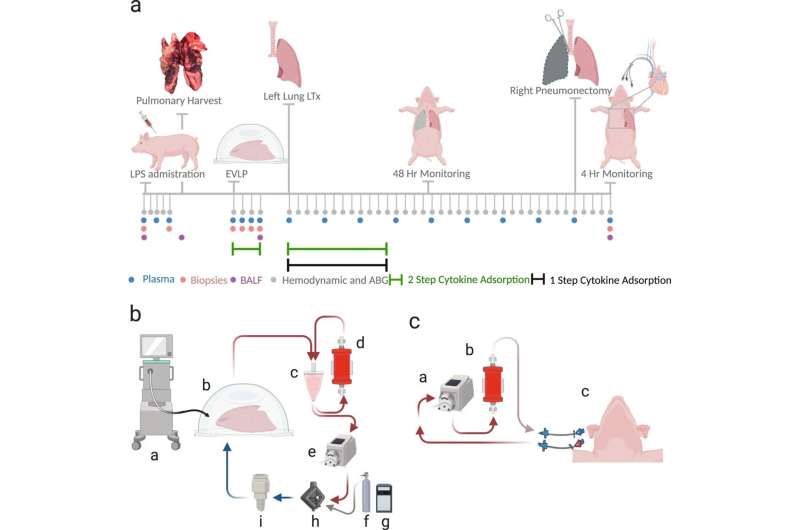

In their study on pigs, the researchers investigated the effects of reducing the levels of cytokines in lungs. Cytokines are small proteins that are produced by specific cells of immune system.

The function of the lungs was reduced before transplant so that the lungs developed acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). By doing this, the lungs acquired injuries similar to those of donor lungs in humans. In ten cases the donor lung was treated—either before and after transplant or only after transplant. Six cases composed a control group and were not given any treatment.

“The results show that the lung function was restored to a higher capacity than before thanks to the reduced levels of cytokines. We could also see that the lungs were functioning better after the transplant and that complications during the first 48 hours after transplant was reduced,” says Lindstedt.

About 50 to 60 lung transplants are performed each year at Skåne University Hospital in Lund and Sahlgrenska University Hospital in Gothenburg. The hope is that the number will increase thanks to the new treatment.

“This will not work on all donor lungs but if we can use it on some of the donor lungs that are discarded today, it could be of great significance for patients on the waiting list for a transplant. We hope to create the needed prerequisites to save more patients,” Lindstedt says.

To be able to conduct the study, a special unit was created within the Department of Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgery, Anesthesia and Intensive Care at Skåne University Hospital. The unit brought together all the competencies needed for the study.

“This study would not be possible without the great efforts of different clinical specialties, such as thoracic surgeons, anesthesiologists, perfusionists, operating room nurses and anesthesiology nurses.”

The study results, which are published in Nature Communications, are the basis of a newly started clinical pilot study.

“We have started to include the first patients in the pilot study at Skåne University Hospital in Lund. The whole study consists of 20 transplants, half of which will be treated to reduce the cytokine levels, and the rest will be treated in the conventional way. If we get positive results, we will expand the study and include 120 transplants nationally,” Lindstedt concludes.

Lund University