The liver is the all-important organ behind processing of various substances we put into our bodies, from food and drink to alcohol and drugs. When things go awry with the liver, the consequences can be deadly. At the root of many liver diseases, from hepatitis to Non-Alcoholic SteatoHepatitis, commonly known as NASH, is scarring, otherwise known as liver fibrosis—and currently, there are no drugs available to treat this scarring.

Researchers are investigating the root causes of liver fibrosis in the hopes of identifying potential targets for drugs in the future. A U-M study identifies a molecule behind the runaway growth of bile duct cells inside the liver.

“Under disease conditions in the liver, there is injury to the bile duct cells,” said Liangyou Rui, Ph.D., the Louis G. D’Alecy Collegiate Professor of Physiology. “The liver has to constantly regenerate new bile duct cells, which sometimes become malfunctional and causes inflammation and scarring.”

This excessive bile duct production, Rui explains, has a special name: ductular reaction. Patients with ductular reaction have more disease complications and poorer outcomes.

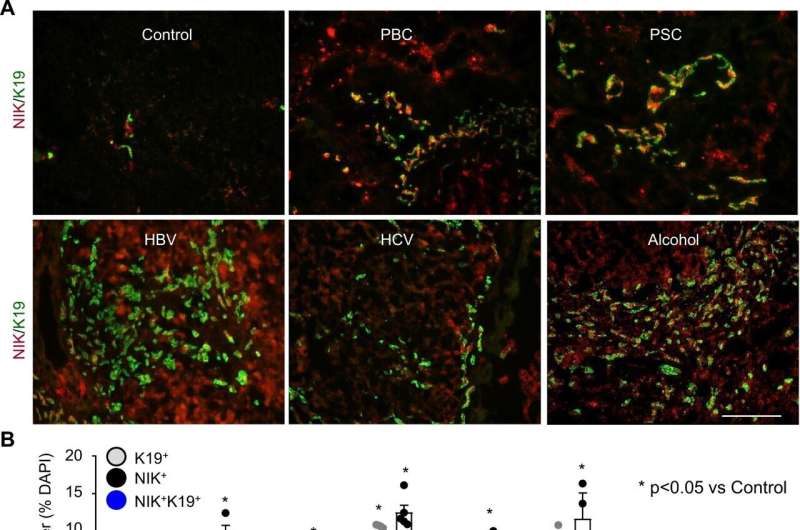

In the paper, published in the journal Nature Communications, they describe a molecule called NIK that is highly activated in the malfunctioning bile duct cells. Using a genetically modified mouse model, they removed the NIK gene inside the bile duct cells.

“When removed, you prevent all of those bad things from happening,” said Rui. Furthermore, treating normal mice with NIK inhibitors, molecules that can block the action of NIK, improved their liver disease.

How does NIK cause disease? Under normal circumstances, NIK promotes the regeneration of bile duct cells in response to the various toxic substances that the liver is exposed to while carrying out its normal duties. However, certain viruses, drugs, or other insults can hijack this normal restorative function and lead to excessive growth and the ductular reaction, as well as the secretion of inflammatory mediators that lead to scarring.

The team hopes to work with collaborators at U-M and elsewhere to develop new NIK-inhibitors to turn off this scarring process. The findings also have potential use as a therapy for a certain type of liver cancer called cholangiocarcinoma, which accounts for one third of all liver cancers and has very limited treatment options.

Kelly Malcom, University of Michigan