New research from the University of Cincinnati bolsters a hypothesis that Alzheimer’s disease is caused by a decline in levels of a specific protein, contrary to a prevailing theory that has been recently called into question.

UC researchers led by Alberto Espay, MD, and Andrea Sturchio, MD, in collaboration with the Karolinska Institute in Sweden, published the research on Oct. 4 in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Questioning the dominant hypothesis

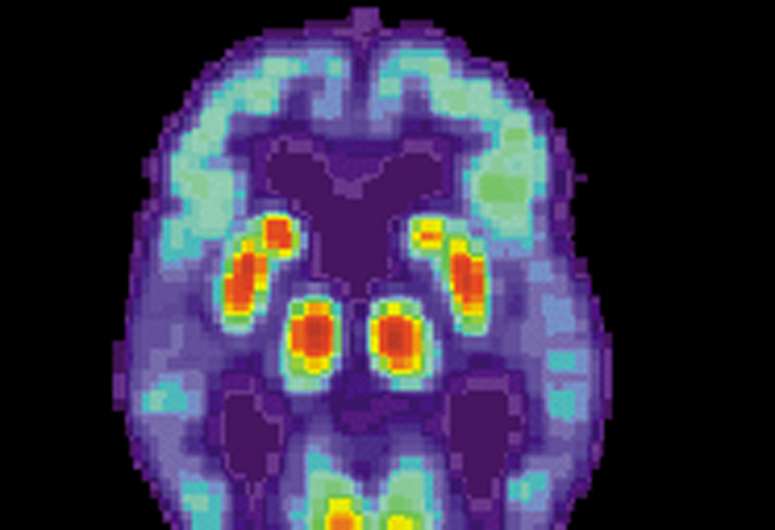

The research is focused on a protein called amyloid-beta. The protein normally carries out its functions in the brain in a form that is soluble, meaning dissolvable in water, but it sometimes hardens into clumps, known as amyloid plaques.

The conventional wisdom in the field of Alzheimer’s research for more than 100 years stated that Alzheimer’s was caused by the buildup of amyloid plaques in the brain. But Espay and his colleagues hypothesized that plaques are simply a consequence of the levels of soluble amyloid-beta in the brain decreasing. These levels decrease because the normal protein, under situations of biological, metabolic or infectious stress, transforms into the abnormal amyloid plaques.

“The paradox is that so many of us accrue plaques in our brains as we age, and yet so few of us with plaques go on to develop dementia,” said Espay, professor of neurology in the UC College of Medicine, director and endowed chair of the James J. and Joan A. Gardner Family Center for Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders at the UC Gardner Neuroscience Institute and a UC Health physician. “Yet the plaques remain the center of our attention as it relates to biomarker development and therapeutic strategies.”

Sturchio noted that many research studies and clinical trials over the years have aimed at reducing amyloid plaques in the brain, and some have lessened plaques, but until the September 27 announcement of a positive trial by Biogen and Eisai (lecanemab), none slowed the progression of Alzheimer’s disease. More importantly, in support of their hypothesis, in some clinical trials that reduced the levels of soluble amyloid-beta, patients showed worsening in clinical outcomes.

“I think this is probably the best proof that reducing the level of the soluble form of the protein can be toxic,” said Sturchio, first author of the report and adjunct research instructor at UC’s College of Medicine. “When done, patients have gotten worse.”

Research results

Previous research from the team found that regardless of the buildup of plaques in the brain, people with high levels of soluble amyloid-beta were cognitively normal, while those with low levels of the protein were more likely to have cognitive impairment.

In the current study, the team analyzed the levels of amyloid-beta in a subset of patients with mutations that predict an overexpression of amyloid plaques in the brain, which is thought to make them more likely to develop Alzheimer’s disease.

“One of the strongest supports to the hypothesis of amyloid toxicity was based on these mutations,” Sturchio said. “We studied that population because it offers the most important data.”

Even in this group of patients thought to have the highest risk of Alzheimer’s disease, the researchers found similar results as the study of the general population.

“What we found was that individuals already accumulating plaques in their brains who are able to generate high levels of soluble amyloid-beta have a lower risk of evolving into dementia over a three-year span,” Espay said.

The research found that with a baseline level of soluble amyloid-beta in the brain above 270 picograms per milliliter, people can remain cognitively normal regardless of the amount of amyloid plaques in their brains.

“It’s only too logical, if you are detached from the biases that we’ve created for too long, that a neurodegenerative process is caused by something we lose, amyloid-beta, rather than something we gain, amyloid plaques,” Espay said. “Degeneration is a process of loss, and what we lose turns out to be much more important.”

Next steps

Sturchio said the research is moving forward to study if increasing the levels of soluble amyloid-beta in the brain is a beneficial therapy for patients with Alzheimer’s.

Espay said it will be important to ensure that the elevated levels of the protein introduced into the brain do not then turn into amyloid plaques, since the soluble version of the protein is needed for normal function to make an impact in the brain.

On a larger scale, the researchers said they believe a similar hypothesis of what causes neurodegeneration can be applied to other diseases including Parkinson’s and Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, with research ongoing in these areas as well.

For example, in Parkinson’s disease, a normal soluble protein in the brain called alpha-synuclein can harden into a deposit called a Lewy body. The researchers hypothesize that Parkinson’s is not caused by Lewy bodies aggregating in the brain, but rather by a decrease in levels of normal, soluble alpha-synuclein.

“We’re advocating that what may be more meaningful across all degenerative diseases is the loss of normal proteins rather than the measurable fraction of abnormal proteins,” Espay said. “The net effect is a loss not a gain of proteins as the brain continues to shrink as these diseases progress.”

Espay said he envisions a future with two approaches to treating neurodegenerative diseases: rescue medicine and precision medicine.

Rescue medicine looks like the current work, studying if boosting levels of key proteins like amyloid-beta leads to better outcomes.

“Interestingly, lecanemab, the anti-amyloid drug recently reported as beneficial, does something that most other anti-amyloid treatments don’t do in addition to reducing amyloid: It increases the levels of the soluble amyloid-beta,” Espay said.

Alternatively, precision medicine entails going deeper to understand what is causing levels of soluble amyloid-beta to decrease in the first place, whether it is a virus, a toxin, a nanoparticle or a biological or genetic process. If the root cause is addressed, the levels of the protein wouldn’t need to be boosted because there would be no transformation from soluble, normal proteins to amyloid plaques.

Espay said precision medicine would take into account the fact that no two patients are alike, providing more personalized treatments. The researchers are making progress in precision medicine through the Cincinnati Cohort Biomarker Program, a project aiming to divide neurodegenerative diseases by biological subtypes in order to match therapies based on biomarkers to those most likely to benefit from them.

“The Cincinnati Cohort Biomarker Program is dedicated to working toward deploying the first success in precision medicine in this decade,” Espay said. “By recognizing biological, infectious and toxic subtypes of Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s, we will have specific treatments that can slow the progression of those affected.”

University of Cincinnati