The purpose of a flight may affect an individual’s willingness to compensate for carbon emissions, according to a new study.

“Our thinking is not strictly rational when it comes to carbon offsetting. Emotions and systematic errors in thinking also play a role,” says Patrik Sörqvist, professor in psychology.

The idea behind carbon offsetting is that the one causing the carbon emission should pay for a reduction in carbon emissions somewhere else, for instance by buying allowances, investing in forest planting or in development of renewable energy.

The question is, however, if the choice to compensate for carbon emissions is determined only by the amount of carbon emissions caused, or if there are other motivating reasons.

In a recent study published in Frontiers in Psychology, researchers from University of Gävle have explored psychological mechanisms, how moral motives behind actions affect willingness for carbon offsetting in two experiments.

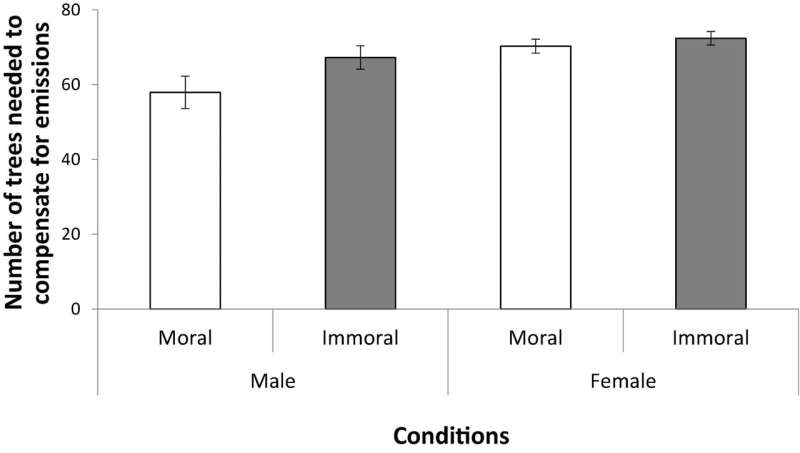

In the first experiment, 500 participants were asked to decide how many trees needed to be planted to compensate for a flight that caused a specified amount of carbon emissions. Half of the participants were told that the purpose of the flight was to send refugee children to a war zone, while the other half were informed that the purpose was the opposite: to save refugee children from that war zone. The amount of carbon emissions was the same in both scenarios.

The experiment showed that although carbon emissions were the same, participants who were faced with a flight undertaken for immoral reasons, that is transporting children to a war reason, felt that the compensation for carbon emissions should be higher than participants who were told that the flight was undertaken for a good cause.

In the second experiment, the participants’ knowledge about climate and emissions were considered. The researchers also added a neutral purpose of the flight to the immoral and moral ones.

The purpose of the flight still affected the requirement for carbon offsetting, even for participants with good knowledge of carbon emissions, while a neutral or a good cause for the flight didn’t significantly affect the amount of carbon offsetting required in the participants’ minds. However, exactly like in the first experiment, trips undertaken for immoral purposes were clearly seen as requiring more compensation for carbon emissions.

“The results show that pity determines if, and how much, we compensate for carbon emissions, although it should be a matter of pure mathematics if and how much we should compensate for a certain flight,” says Patrik Sörqvist, professor in psychology and one of the authors of the study.

The study also strengthens the thesis in prior research: people strive for balance on a moral account. This striving for balance, which privileges balance in our own moral behavior, seemingly also covers matters that we are not actively involved in.

“A moral behavior, like donating to charity in the shop, is often followed by a more immoral act. An example would be not to choose organic products after having deposited cans. The same kind of systematic errors in thinking seems to play a part in carbon offsetting as well; people take matters that have nothing to do with the amount of carbon emissions into account,” Patrik Sörqvist says.

University of Gävle