A probiotic bacterium called Lacticaseibacillus rhamnosus HA-114 prevents neurodegeneration in the C. elegans worm, an animal model used to study amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

That’s the finding of a new study at Canada’s CHUM Research Center (CRCHUM) led by Université de Montréal neuroscience professor Alex Parker and published in the journal Communications Biology.

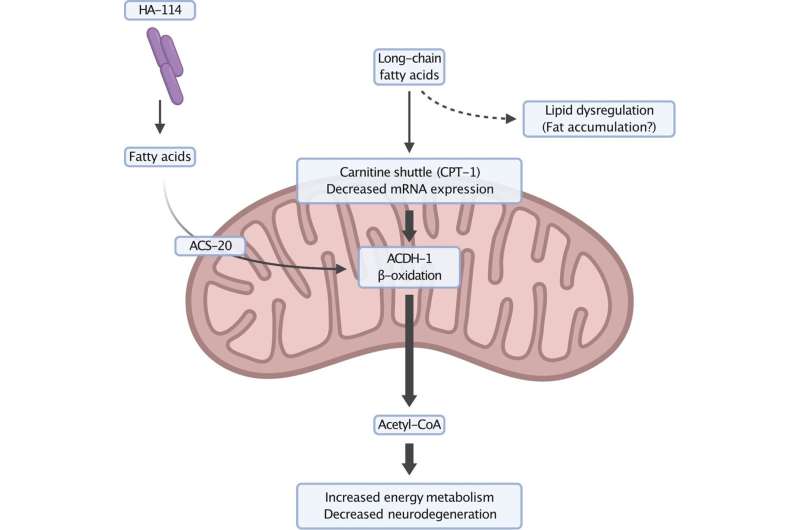

He and his team suggest that the disruption of lipid metabolism contributes to this cerebral degeneration, and show that the neuroprotection provided by HA-114, a non-commercial probiotic, is unique compared to other strains of the same bacterial family tested.

“When we add it to the diet of our animal model, we notice that it suppresses the progression of motor neuron degeneration,” said Parker, the study’s lead author. “The particularity of HA-114 resides in its fatty acid content.”

By enabling the transmission of signals to muscles so that they contract, motor neurons, which are nerve cells, allow us to move our body at will.

People with ALS see a gradual deterioration of their motor neurons. This makes them lose their muscular ability, to the point of total paralysis, with an average life expectancy of only 3 to 5 years after diagnosis.

Nearly 3,000 people in Canada have ALS.

“Recent research has shown that the disruption of the gut microbiota is likely involved in the onset and progression of many incurable neurodegenerative diseases, including ALS,” explained Parker.

Identifying neuroprotective bacterial strains could form a basis for new therapies.

A matter of diet

Central to this scientific project is Audrey Labarre, the study’s first author, a postdoctoral fellow working hard to advance research on ALS by focusing on motor neuron degeneration in C. elegans worms.

Measuring only one millimeter in length and sharing 60% of their genetic makeup with humans, these nematodes were genetically modified with ALS-associated genes for the purposes of the CRCHUM research.

To study the neuroprotective effects of a probiotic-based dietary supplement on this animal model, Labarre tested a total of 13 different bacterial strains and three strain combinations.

HA-114 stood out from the pack. The action of the probiotic helped reduce motor disorders in models with ALS and also Huntington’s disease, another neurodegenerative disease.

Two genes at play

Relying on data from the genetic study, genomic profiling, behavioral analysis and microscopy images, the scientific team identified two genes, acdh-1 and acs-20, which play a key role in this neuroprotective mechanism.

They were able to accomplish this meticulous work thanks to collaborations with Martine Tétreault, a CRCHUM researcher, and Matthieu Ruiz, a researcher at the Montreal Heart Institute Research Center.

Existing in equivalent forms in humans, both genes are involved in lipid metabolism and beta-oxidation, a process through which fatty acids are broken down into energy in the mitochondria, the true cellular power plants.

“We believe that fatty acids supplied by HA-114 enter the mitochondria through an independent, non-traditional pathway, said Parker. In doing so, they restore balance to impaired energy metabolism in ALS and lead to a decrease in neurodegeneration.”

The researcher’s team is now conducting similar studies on an animal model more complex than the C. elegans worm: the mouse.

They will then validate in a clinical setting whether HA-114 could be a therapeutic complement to current ALS treatments. The advantage is that probiotics, unlike drugs, produce few side effects, they say.

To this end, a Canada-wide clinical study headquartered at the CRCHUM and led by ALS clinic director Dr. Geneviève Matte will be conducted with 100 subjects, starting in the spring of 2023.

Bruno Geoffroy, University of Montreal Hospital Research Centre