Psychological trauma from extreme weather and climate events, such as wildfires, can have long-term impacts on survivors’ brains and cognitive functioning, especially how they process distractions, my team’s new research shows.

Climate change is increasingly affecting people around the world, including through extreme heat, storm damage and life-threatening events like wildfires. In previous research, colleagues and I showed that in the aftermath of the 2018 fire that destroyed the town of Paradise, California, chronic symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety and depression were highly prevalent in the affected communities more than six months after the disaster.

We also found a graded effect: People whose homes or families were directly affected by fire showed greater mental health harm than those where who were indirectly effected, meaning people who witnessed the event in their community but did not have a personal loss.

In the new study, published Jan. 18, 2023, our team at the Neural Engineering and Translation Labs, or NEATLabs, at the University of California San Diego, wanted to understand whether the symptoms of climate change-related trauma translate to changes in cognitive functioning—the mental processes involved in memory, learning, thinking and reasoning.

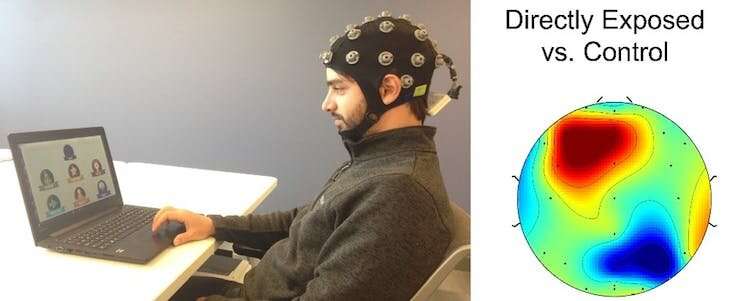

We evaluated subjects’ cognitive functioning across a range of abilities, including attention; response inhibition—the ability to not respond impulsively; working memory—the ability to maintain information in mind for short periods of time; and interference processing—the ability to ignore distractions. We also measured their brain function while they performed cognitive tasks, using brain wave recordings obtained from electroencephalography, or EEG.

The study included three groups of individuals: people who were directly exposed to the fire, people who were indirectly exposed, and a control group with no exposure. The groups were well matched for age and gender.

We found that both groups of people exposed to the fire, either directly or indirectly, dealt with distractions less accurately than the control group.

We also found differences in the brain processes underlying these cognitive differences. People who were exposed to the wildfire had greater frontal lobe activity while dealing with distractions. The frontal lobe is the center for the brain’s higher-level functions. Frontal brain activity can be a marker for cognitive effort, suggesting that people exposed to the fires may be having more difficulty processing distractions and compensating by exerting more effort.

With climate change fueling more disasters, it is incredibly important to understand its impacts on human health, including mental health. Resilient mental health is what allows us to recover from traumatic experiences. How humans experience and mentally deal with climate catastrophes sets the stage for our future lives.

There are strategies people can use to help reduce the stress. Psychosocial research suggests that practicing mindfulness and developing healthy lifestyles, with regular exercise and enough sleep, can protect mental well-being in these scenarios, along with developing strong social bonds.

There is much work to be done to understand if the effects we found are replicable in large sample studies. In this work, we focused on a total of 75 study participants. Scientists also need to understand how these effects evolve as climate disasters like wildfires occur more often.

We are also pursuing research with community partners to implement interventions that can help alleviate some the impacts we observed on brain and cognitive functioning. There is no one-size-fits-all solution—each community must find the resiliency solutions that work best in their environmental context. As scientists, we can help them understand the causes and point them to solutions that are most effective in improving human health.

Jyoti Mishra, The Conversation