Global health equity means more than working toward good health around the world. It also means fairness for researchers.

Too often, the field favors those based in high-income countries (HICs), many of whom gather data in the Global South without crediting local collaborators or ensuring them fair access to resources and publication—an unethical practice sometimes called “parachute research.”

That needs to change—and there are practical steps to take, says a team of Yale and Cameroonian researchers.

The team has created a checklist for global health scholars to ensure fairness during the entire research process, from study design and funding through data collection, writing, and publication.

“We really wanted to make a concrete, usable document that folks pull out at the very beginning of thinking about a study,” said Dr. Sunil Parikh, associate professor of epidemiology (microbial diseases) at the Yale School of Public Health and of infectious diseases at the Yale School of Medicine.

It’s a way to help researchers pursue locally derived, locally applicable solutions to global health problems, he explained.

“Living in New Haven, Connecticut, I am not the best person to figure out the optimal way to advance malaria control in Yaoundé, Cameroon,” Parikh said. “The ideas and probably the most impactful solutions are going to come from the voices of folks working there in that environment.”

“In the U.S., in schools of public health and medicine, sometimes one assumes, ‘We here, we Americans, we have this idea, and it’s the best idea,'” said co-author Dr. Daniel Z. Hodson, MD ’21, who studied in Cameroon under an exchange program Parikh helped to set up. “What’s being overlooked is that somewhere in a lab or in a village, or in [the cities of] Yaoundé or Dakar, there are ideas that can help not only the population of Africa but the U.S. and the rest of the world as well.”

The checklist is aspirational, the researchers say. But it opens up a necessary conversation.

“We never will be able to arrive at perfect equity,” said co-author Yannick Mbarga Etoundi, PharmD, a Cameroon-based pharmacologist who spent time in Parikh’s lab learning molecular epidemiology techniques. “But each time Daniel and I work together, we are always reflecting and asking ourselves, ‘How should things have been a little better?'”

Steps toward equity

Among the Douala Equity Checklist’s 20 items are recommendations to:

- Pair principal investigators and trainees in HICs with counterparts in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs). Build institutional relationships in this way.

- Make sure everyone stands to gain by participating.

- Make sure all parties are familiar with the history of global health, especially of projects conducted in and innovations originating in the LMIC.

- Offer everyone involved in a study basic language training.

- Protect the LMIC principal investigator’s time to do research, but don’t incentivize brain drain.

- Ensure equal access to data, online databases, software, statistics and manuscript training, and other relevant resources.

- Compensate LMIC field workers fairly.

- Meaningfully alternate who is lead author in publications or seek joint co-authorship.

- Publicize results where the research was conducted.

These points challenge wealthy institutions to surrender some of their own power, the authors write. That can mean, for example, designing budgets that ensure scientists in LMICs can travel to HIC institutions for training.

Other parties also have a part to play in improving equity, according to the authors. Philanthropists in LMICs should bolster research funding in their home countries. Conference organizers should make interpreters available. And journals should publish entire articles—not just abstracts—in relevant languages as well as English.

“There is a lot of research in Africa that is not heard, that is not published in scientific journals. It stays in our notebooks, in our computers, and is never published,” said Mbarga Etoundi. “If one arrives truly at that level of equity, that could allow numerous young Africans to emerge on the international scene, show the work they’ve done, and make themselves heard.”

Fewer, but more equitable collaborations, the authors write, are likely to be more sustainable in the long run.

“We need to realize that we have no choice but to work toward equity,” added co-author Yap Boum II, a Cameroon-based epidemiologist and longtime collaborator with Parikh. “We need each other.”

Unfairness for some hurts everyone

Making sure global health scholarship is equitable takes active effort, because the field is dogged by long-standing inequities that originate in colonialism.

Funding imbalances that favor scholars in HICs, exploitation of scholars in LMICs, and the overwhelming dominance of English-language journals are among the problems contributing to inequities today.

“There’s a problem when, for example, Cameroon can be considered a base for collecting data for exporting to the U.S., France, et cetera. And in addition, these data are presented in a language Francophone Africans cannot understand,” Mbarga Etoundi said. “It’s a double defeat, in effect.”

Such unfairness not only disadvantages health scholars in LMICs like Cameroon, it also slows the progress of research, which in a globally interconnected era hurts everyone.

In 2017, for example, researchers in Nigeria began to warn the world about an outbreak of mpox (formerly called monkeypox) in which the disease behaved in unfamiliar and worrisome ways.

But these warnings were met with little interest and few resources from HICs. Deaths in Africa went largely unnoticed by the West until the outbreak left the region and traveled around the world, catching many countries flat-footed. Global health inequity had in effect hampered global health responses to the 2022 mpox outbreak.

Had everyone been on the same page at that time, Boum said, “we [would] already have good diagnostics. We’d already have [an mpox-specific] vaccine.”

Collaborations built to last

Parikh and Boum have been engaged in malaria collaborations in Africa for decades, and they have made research equity a cornerstone of their collaborative work. The two professors began an exchange program in which each mentored a trainee from the other’s institution and where the trainees would work together. Parikh mentored Mbarga Etoundi, and Boum mentored Hodson.

The younger scholars worked together in person on malaria research, first in Cameroon and later at Yale. Each hosted the other in his home, and both took pains to improve their language skills.

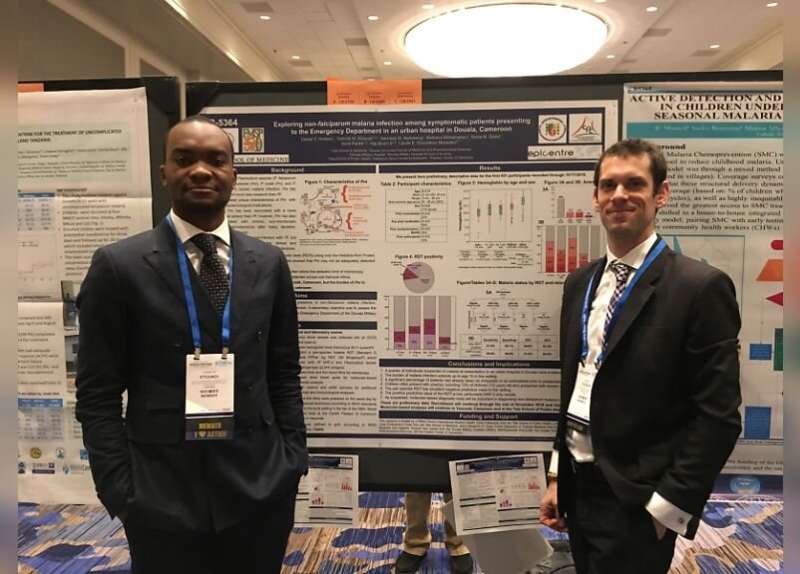

In 2018, Hodson and Mbarga Etoundi presented a poster at the American Society of Tropical Medicine & Hygiene in New Orleans. In 2022, their first joint publication appeared in the Malaria Journal. And they’ve built a lasting friendship: recently, Hodson attended Mbarga Etoundi’s wedding.

When conducting public health research, Hodson said, he asks himself, “‘Would it be good for my grandmother, and would it be good for Yannick’s grandma?'”

Boum, for his part, is helping to develop an app called The Village to help connect researchers around the world. As he puts it, “It will take a village to grow global health scientists.”

“If the house of my neighbor is burning, I have to go and support him because if I don’t, the fire from his house will come to mine,” Boum said. “This solidarity is what we need in global health, and even beyond.”

The article appeared January 18 in PLOS Global Public Health.

Jenny Blair, Yale University