Wash your hands. Wear a high-quality mask. Keep six feet between you and others. Meet outside when possible.

For nearly three years, the public has been inundated with rules, regulations and suggestions from public health officials on the best way to stay safe amid the COVID-19 pandemic. But with so many rules, and little direction about which matter more, people have been left to guesswork, which may have cost lives.

Economist Ori Heffetz, associate professor in the Samuel Curtis Johnson Graduate School of Management, and a colleague conducted an experiment with nearly 700 people in three countries to gauge the public’s perception of relative risk factors.

Among the conclusions: Talking 14 minutes longer was thought to be as risky as standing a foot closer; being indoors was thought as risky as standing three feet closer outdoors; and removing a properly worn mask, by either party, was thought as risky as standing four to five feet closer.

“Estimating Perceptions of the Relative COVID Risk of Different Social-Distancing Behaviors From Respondents’ Pairwise Assessments” published Feb. 7 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Heffetz’s co-author was Matthew Rabin, the Pershing Square Professor of Behavioral Economics at Harvard University.

Heffetz and Rabin wanted to investigate the idea of tradeoffs in the context of people making decisions regarding their health.

“We wondered whether doctors and health officials are too reticent to indicate the relative importance of different measures,” said Heffetz, who’s also a professor at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and a research associate at the National Bureau of Economic Research.

“Imagine someone talking to their dentist, where they ask if it’s more important to floss twice a day or brush more often,” he said. “And the dentist always tells them, ‘Do both.’ But we want to understand what’s a big deal, what’s not so big, how do they compare?”

Their goal in this work: Helping to transform messaging, regarding COVID and other health and non-health domains, to more closely resemble the way most people make decisions.

“Think about weight loss, and the tradeoffs people make,” Heffetz said. “Nobody says, ‘Don’t eat anything but leaves.’ They’ll say, ‘Have your cup of coffee without cream, you’ll save so many calories,’ or ‘Indulge, and then spend two hours at the gym.’ We have a metric—calories—and we can use it to price things. And then we make our decisions. We can make our tradeoffs.”

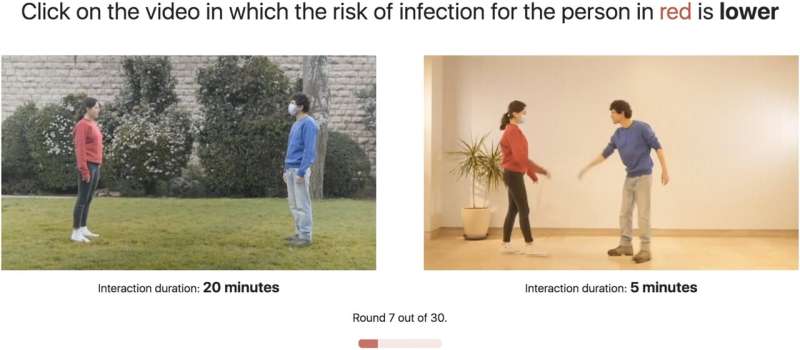

For their experiment, conducted during the spring and summer of 2021, Heffetz and Rabin showed 676 online respondents in the U.S., the United Kingdom and Israel 30 pairs of five-second videos of acquaintances meeting. Respondents were asked to judge, for one of the two people designated, which of the two scenarios in each pair was riskier.

From their responses, the researchers were able to estimate people’s perceptions of how risks changed by the features of the conversation. They used videos rather than verbal descriptions in order to let people judge each depiction on their own, without any prompting.

“We wanted to do something that looks to respondents as realistic as possible,” Heffetz said. “And then we don’t draw their attention to any specific thing, we just show them the scenario. And if they notice the mask, the distance between the subjects, the cough or the hug … we let them pick what they think is important and then see what emerges.”

Heffetz and Rabin wondered if the messaging from health officials could have benefited from a more nuanced set of guidelines.

“We only saw the list of things—’Do all of these things,'” Heffetz said. “But which one is more important, and less important? It was hard to get an answer. That may have cost lives, because people may have made the wrong decisions.”

But like the dentist, Heffetz said, health officials don’t want to tell you that one behavior may be more important than another. In a perfect world, people do them all because they’re all important.

“I’m sure some people do them all, but most of us often have to make a decision between two imperfect bundles,” he said. “And we would really like to know which one the professionals consider is the better choice in this case.

“Our results may suggest a major health-risk public-communications failure in terms of how behaviors compare in relative risk,” Heffetz said. “We think this would be something that maybe policymakers would listen to.”

Tom Fleischman, Cornell University