In most workplaces, one of the best ways to train and develop employees professionally is by providing effective feedback. Feedback that is timely, specific, and actionable has been proven to improve learner motivation, engagement, and perceived support, and lower rates of burnout.

But who tends to get the most useful feedback? When Penn researchers looked at factors that might lead to gender disparities in emergency medicine (EM), they found that gender played a role in both the content and quality of feedback.

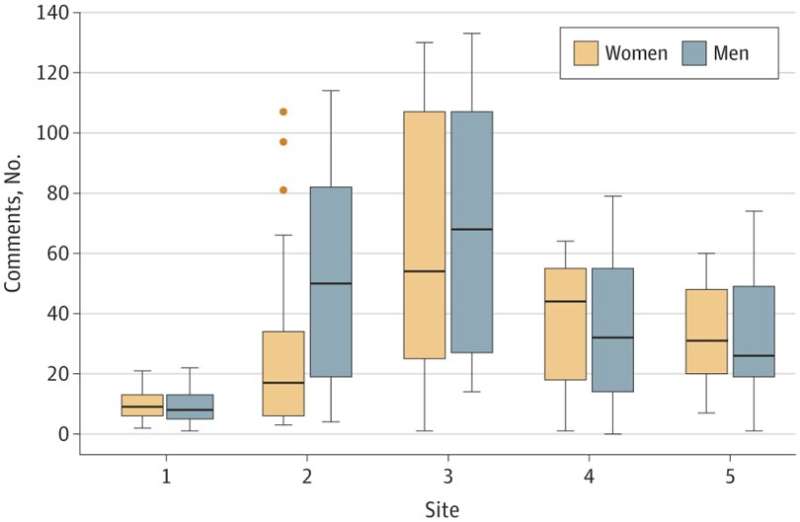

In the study, published recently in JAMA Network Open, researchers analyzed narrative comments for EM residents from EM attending physicians over a three-year period, across five EM training programs nationwide. This specialty is farther behind academic medicine as a whole in achieving gender parity, with women representing only 35.9% of residents, 28.3% of faculty, and 11% of department chairs, compared to representing 47.3% of residents, 36.3% of faculty, and 21.9% of department chairs across all specialties.

Lead author Mira Mamtani, MD, MSEd, an associate professor of Emergency Medicine in the Perelman School of Medicine, associate residency program director at Penn Medicine, and associate director of FOCUS for Health and Leadership for Women, draws upon the findings of the study to offer guidance for providing better feedback.

“Addressing these differences in feedback content and quality would not only better train women residents, but also improve training for residents of all genders,” she said. “Not only could our findings be applied across medical specialties, but in any workplace who wants to provide better training to their employees.”

Make sure to give enough feedback

In Penn Medicine’s EM residency program, residents receive feedback both verbally in-person, as well as via online written assessments. The study Mamtani led focused on these online assessment forms. Feedback should be given at the end of each clinical shift, and residents typically have access to it within a week. Residency directors, like Mamtani, are also able to view the assessments, and will go over the comments individually during a resident’s annual review.

“The comments that are specific, actionable, and objective help us develop an individual plan for the learner that includes which resources would work best for their growth and development, creating better physicians for our workplace,” said Mamtani. “When feedback is vague or doesn’t include comments at all, it can be frustrating for the resident, and makes determining next steps difficult.”

In the study period, male attending physicians submitted assessments rating residents’ competency without providing any feedback comments more often than female attending physicians. Ideally, learners should receive feedback after each clinical shift, so that they are able to improve their performance with subsequent patient encounters. Male faculty also provided non-specific feedback, like “great work,” more often than female faculty. Mamtani suggests that not providing feedback is a missed opportunity for assessing and improving skills.

“A person can’t know what they need to improve on if no one tells them,” Mamtani says. “If some attending physicians are only scoring residents’ competency but not explaining why, that resident won’t know what areas they should work on.”

Mamtani also underscores that providing feedback is valuable work that should be rewarded. “Providing feedback is integral to the growth and development of learners, but it’s not a skill that considered in tenure or promotion processes in most professions,” she said. “Institutions should take it into consideration when evaluating faculty for promotions, which could also incentivize folks to improve the feedback they’re already giving.”

Be as specific as possible

The study revealed differences in the specificity of feedback residents received as well. Men received more feedback on specific cases or behaviors, while women received more feedback on personal attributes, like adaptability and assertiveness.

For example, comments for a man read, “Had a scare where they looked at the wrong dated CT on a patient which was negative when the most recent CT had a head bleed…we discussed the importance of right patient, right date, right time.” This comment addresses a specific case, the issue that occurred, and how it was corrected.

In contrast, a comment for a woman said, “resident is reliable but at times more independent than I prefer, and it makes me not always trust them—I haven’t seen them do harmful things, but I’ve had conversations with them where they dig their heels in, nearly refuses to act on my suggestion and takes a righteous stand.” Rather than address a specific scenario where the attending physician could have proposed a different course of action that the resident could correct in the future, they only discuss her demeanor in general, leaving her with ambiguous next steps.

“When the specific case where there could be improvements is highlighted, the trainee can see the skill in context with their work, and build competencies from there,” said Mamtani.

Focus on objective skills and outcomes

Investigators found that among the comments that addressed resident performance, more men were assessed as performing above level, while more women were assessed as performing below level.

Investigators also found that among the residents assessed as below level performance, more than 5% of trainees who were women received comments that their procedural skills were below level, and that comments for these trainees often also mention confidence, or lack thereof. For instance, one comment directed at a women trainee read, “resident appears to have solid clinical skills but has gotten flustered when procedures are required.”

To contrast, comments directed at men who were assessed as below level included specific actionable items without any mention of confidence. For instance, “the last shift we worked together you missed a few things including…getting an opening pressure on a transplant patient in whom you were performing a lumbar puncture.”

“What is really interesting about this study is that among women residents, it is their perceived lack of confidence in procedures, and not the actual outcome of the procedure, that is leading to poorer ratings,” said Mamtani. “And perhaps some trepidation with procedures is appropriate, as procedures are high stakes and can lead to life-threatening complications.”

Mamtani suggests that one way to break out of this pattern would be to assess residents with more objective parameters. For example, a recent study identified that using checklist-based procedural evaluations may mitigate gendered assessments. Alternatively, assessment of procedural competency could be based on procedural outcomes, or clinical based competency could include discussion of patient outcomes or care patterns. Interventions such as real-time nudges while completing narrative comments and faculty training sessions can also be explored to address this critical need.

“The tools we currently use may not be inherently biased, but we may be interpreting them through a biased lens,” Mamtani said. “When we use tools that focus on objectives skills and outcomes, there’s less room for bias to creep in.”

A rising tide lifts all boats

While addressing gender biases helps women, Mamtani stresses that providing high quality, objective feedback benefits trainees and faculty of all genders.

“Being able to give good feedback is a universal skill,” she said. “When we provide better training, we produce more competent individuals, which strengthens our workplace, builds our reputation, and allows us to provide better care to patients.”

Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania