Influenza viruses are becoming increasingly resilient to medicines. For this reason, new active ingredients are needed. Important findings in this regard have been provided by researchers at the University of Münster: for the virus to proliferate, the polymerase of the influenza A virus has to be modified many times through enzymes in the host cells.

The team of researchers was able to produce a comprehensive map of the types of modification. Medicines directed against the enzymes would be resilient to rapid mutations in the virus, thus offering great potential for the future. The study results have now been published in the journal Nature Communications.

Every year, the influenza season presents a challenge to hospitals. Despite having been vaccinated, older people and patients with health problems run a heightened risk of falling prey to a severe bout of influenza. What is especially insidious about influenza viruses is their ability to mutate rapidly, which makes them increasingly resilient to medicines. For this reason, there is an urgent need for new active ingredients in order to be able to continue providing effective treatment for the illness in future.

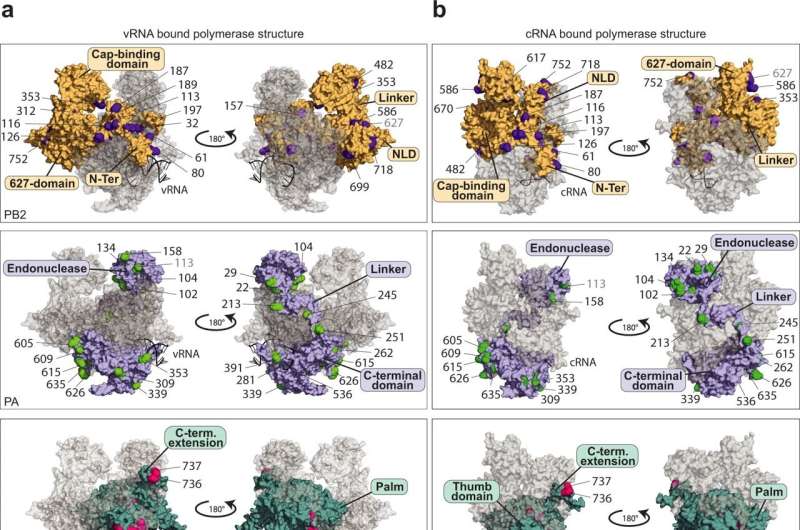

Researchers at the University of Münster have taken an important step in this direction by providing evidence of 59 specific modifications to the polymerase of the influenza A virus, in other words the decisive enzyme responsible for the production of copies of the virus genome. What is special about the modifications described in the study is that they are transmitted by proteins in the host cells—and, in contrast to virus proteins, they cannot mutate rapidly. They therefore represent a promising approach for the production of new medicines.

The influenza A virus polymerase (IAV polymerase) is a highly complex protein which has more than just one function. One of these is that after a structural change it can also make copies of the virus genome (cRNA and vRNA). Without this “switch” of functions, the virus is not able to proliferate.

As Dr. Linda Brunotte and Dr. Franziska Günl and a team of colleagues have now discovered, the IAV polymerase needs proteins from the host cell to act as “molecular switches” and carry out its diverse functions. These proteins are enzymes that dock so-called ubiquitin proteins onto specific places in the polymerase and, as a result, trigger the signal for the switch of functions.

“We were able to produce a map showing 59 positions on the viral polymerase to which ubiquitin was attached through the host cell. These are completely new findings which reveal the Achilles’ heel of the influenza A virus,” explains Dr. Brunotte, who heads a team of researchers at the Institute of Molecular Virology and also initiated the study.

This ubiquitination had a definite influence on the activity of the polymerase at 17 spots. Moreover, one specific position was discovered whose modification represents the signal for the conversion and the associated switch of functions in the polymerase. As a result, Dr. Günl, the lead author of the study, is now looking ahead: “On the basis of our mapping of the ubiquitination, further studies can now research into which enzymes are specifically responsible for the modification of the IAV polymerase. Medicines which are directed against these enzymes would be resistant to mutations in influenza viruses, thus displaying great potential for future treatments.”

Universität Münster