A grape-like structure in the brain called the choroid plexus becomes enlarged and shows increased accumulation of abnormal inflammatory molecular signaling in people with Alzheimer’s disease, according to a new study published in the journal Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

An international team of researchers, including scientists from the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), part of City of Hope, show that these changes appear to be a more extreme or perturbed version of changes seen in the choroid plexus—part of the blood-brain barrier—during normal aging.

The choroid plexus increases in volume with age and Alzheimer’s disease. One striking finding from the study was that “the larger the choroid plexus, the poorer the cognitive performance in those Alzheimer’s patients,” said Gorazd B. Stokin, M.D., Ph.D., principal investigator at the International Clinical Research Center of St. Ann’s University Hospital Brno, Czech Republic, and senior author of the study.

The choroid plexus is a network of blood vessels and cells that produces cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and creates a barrier between CSF and blood circulating throughout the body. Through the production of CSF, the choroid plexus helps maintain the brain’s immune system activation.

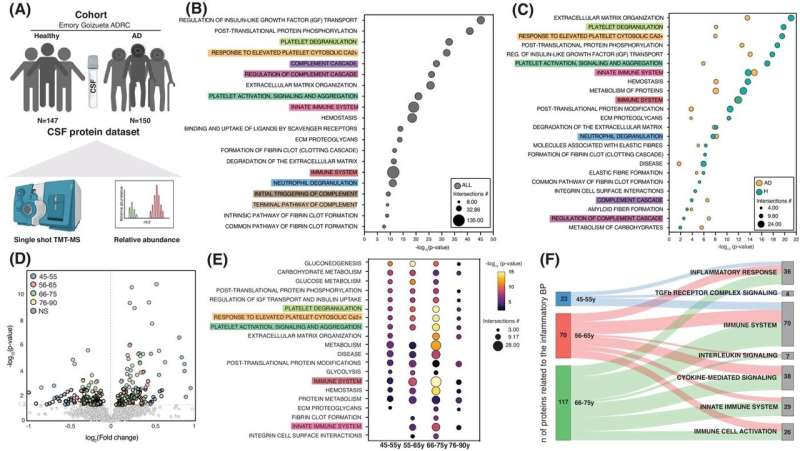

The scientists compared the CSF choroid plexus in healthy individuals and people with Alzheimer’s, as well as patients with other neurological diseases such as acute Lyme disease and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or ALS. They analyzed inflammatory signaling in the CSF, as well as structure and volume changes in the choroid plexus in postmortem brains and in patients using MRI.

Following up on studies that show the choroid plexus can be damaged in aging and Alzheimer’s, Dr. Stokin and his colleagues wanted to focus more deeply on the role that this tissue may play in neuroinflammation in the disease.

The researchers found protein abnormalities and “an aberrant signaling of immune molecules” in the CSF and choroid plexus of people with Alzheimer’s,” said study author Patrick Pirrotte, Ph.D., Director of TGen’s Collaborative Center for Translational Mass Spectrometry.

While these biological changes are also found in normal aging, he noted, they are different from those seen in other neurological disorders examined in the study.

The changes seen in aging and Alzheimer’s patients were most pronounced in the 66–75 years old age group, the researchers found.

“The changes in choroid plexus volume in this group could be related to the recruitment of more inflammatory cells,” said Mária Čarná, Ph.D., of St. Ann’s University Hospital Brno, and the papers first author. “With the help of cognitive performance tests taken by some patients, the team also showed that increased choroid plexus volume was correlated with poorer cognitive performance.”

The researchers cautioned that more work needs to be done to determine whether these changes in the choroid plexus and CSF are causing Alzheimer’s, or whether they reflect the disease state.

Dr. Pirrotte continues to work on potential external risk factors that might exacerbate these changes, “and could accelerate the development of Alzheimer’s Disease,” he said. Last year, for instance, he and his colleagues published a study on how the herbicide glyphosate can increase pro-inflammatory molecules in the brain that may be related to neurodegeneration.

Becky Ham, Translational Genomics Research Institute