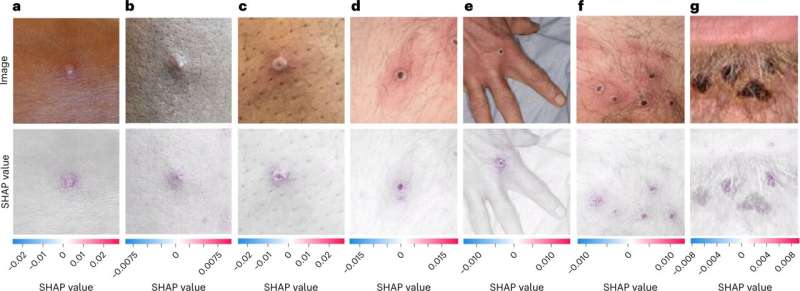

A new app developed by scientists at Stanford Medicine and other institutions can detect skin lesions caused by mpox, previously known as monkeypox, in images with an accuracy of 90%, the researchers found in a study. To analyze images, the app uses a type of artificial intelligence that was trained and evaluated on a large data set of about 130,000 images of various skin conditions.

The free, open-source app, called PoxApp, allows users to take pictures of skin lesions using their smartphones, answer a few questions and receive a risk score with recommendations, such as mpox testing or post-exposure vaccination, in less than five minutes.

“It’s a quick, easy and anonymous way to get a first assessment,” said Alexander Thieme, MD, the lead developer of the app and a visiting scholar in the Department of Medicine from Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin and Berlin Institute of Health. “We are hoping to increase the likelihood that someone sees a doctor due to their skin lesions rather than ignore it.”

Although the app has a high accuracy, it can give false negatives. It’s not a substitute for a physician, Thieme stressed. But the app could reach communities with less access to care and encourage people to visit a doctor.

“Many people seek out medical information on the internet, and much of that may be inaccurate,” Thieme said. “With this app, developed with guidance from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the World Health Organization, we hope to encourage people to seek out care.”

The artificial intelligence methods and the findings of the app were published online in Nature Medicine March 2. The project is a joint effort of the labs of Olivier Gevaert, Ph.D., Tina Hernandez-Boussard, Ph.D., and Pascal Geldsetzer, MD, Ph.D., at Stanford Medicine as well as collaborators at Charité—Universitätsmedizin Berlin and Toronto University Hospital. Thieme is the lead author.

Optimizing results

To calculate your risk score, the app considers whether you have a skin lesion, are experiencing symptoms or had close contact with someone who may have been exposed.

Thieme said the app is anonymous: All the data is analyzed on your device and not sent to an external server. The app gives advice on how to take the best photo to reduce the likelihood of a false negative.

Researchers have found that the app can detect mpox at various stages of the disease. There are four stages of lesions, progressing from flat without fluid, to raised with clear fluid, to deep rashes filled with white fluid, before the lesion scabs over, usually in two to three weeks.

The app offers five different levels of advice, ranging from no action to seeing a doctor immediately. Thieme said that if someone has had contact and symptoms, they should see a doctor.

Users have the option to submit results for research data. Using this data, scientists like Thieme hope to predict future surges in mpox infection and employ an early warning system.

The researchers plan to publish updated versions of the app as users upload more photos. With more data, they anticipate the accuracy of the photo recognition will improve. Because the app is open-source and free, Thieme hopes it will be used around the world, particularly in Africa, where mpox was first identified in the 1970s.

Emily Moskal, Stanford University Medical Center