Ninety years after the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation enacted the discriminatory practice of color-coding neighborhoods by desirability for mortgage lenders, redlined neighborhoods—areas inhabited largely by Black families—continue to suffer poorer health than greenlined, majority-white neighborhoods, which tend to flourish healthwise and financially.

These findings and persisting health and economic inequities between one neighborhood or one zip code and another is explored by Roshanak Mehdipanah and Amy Schulz of the University of Michigan’s School of Public Health.

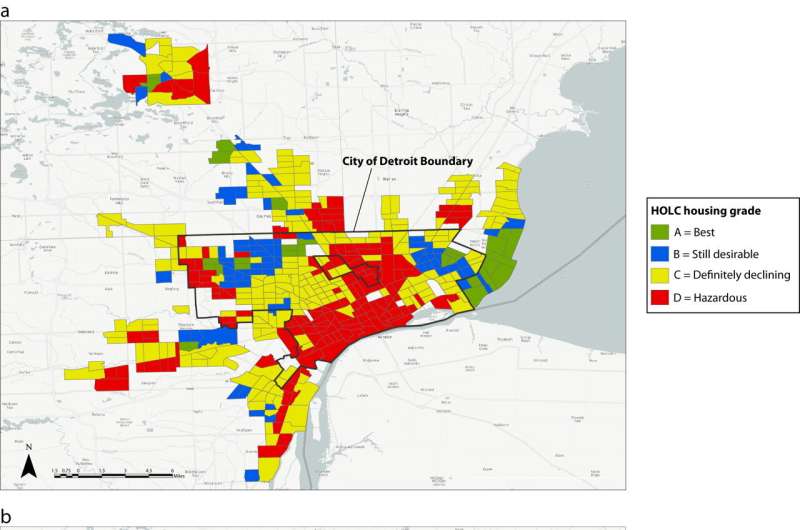

Their research, published in the American Journal of Public Health, mapped 484 census tracts across the Detroit metropolitan area, home to 3.8 million residents. It analyzed associations between the HOLC’s color-coded neighborhoods with a Determinants of Health Equity Index, which uses four well-established domains as predictors of health: economic growth, social and human development, governance and physical environment.

Findings indicate that historically redlined neighborhoods currently score lower on the DOHI compared to neighborhoods with more favorable blue, yellow or green HOLC scores. Because redlined neighborhoods were disproportionately Black and greenlined neighborhoods disproportionately white, these scores reflect structural forces that, over time, have contributed to Black/white inequities in opportunities for health, the researchers say.

Mehdipanah is an associate professor of health behavior and health education, director of Housing Solutions for Health Equity and co-leader of Public Health IDEAS for Creating Healthy and Equitable Cities. Schulz is a University Diversity and Social Transformation Professor and professor of health behavior and health education.

They explain their findings and why understanding the lingering harm of redlining is necessary to repairing the damage of discriminatory policies.

How does your research build on current research on the topic of health inequity and social determinants of health?

Mehdipanah: There is a growing literature that shows associations between historical redlining practices and various negative health outcomes, including preterm birth and mental health issues. Our study provides context on some of the determinants of health that could be driving those associations. We are seeing the continued effects of redlining practices of the 1930s on present-day conditions, including median household income, home ownership and educational attainment.

Could you provide some details?

Mehdipanah: We saw a $60,000 difference in present-day median household income between neighborhoods that were historically greenlined compared to those that were historically redlined. We also see an almost 30% difference in homeownership between these neighborhoods. While historically redlined neighborhoods have experienced significant disinvestment, greenlined areas have accumulated greater benefits in various determinants of health, including education, employment and income.

How could your research findings be used?

Schulz: Our research aims to provide insight on the historical roots of contemporary health inequities. A goal is to inform current conversations about reparations, including those focused on reinvestment in housing, infrastructure and greening—all critical to health.

What could governmental agencies, elected officials, advocates for health equity take away from the research?

Schulz: Our findings highlight the continued effects of discrimination in local policies that govern funding and resource allocation. While a few neighborhoods benefit from investment resulting in greater opportunities for residents’ health and well-being—sometimes called ‘resource hoarding’—historically redlined neighborhoods continue to have fewer opportunities for health and well-being. Stronger responses and protections are needed for residents whose economic well-being and health are at risk due to systematic patterns of disinvestment in predominantly Black Detroit-area neighborhoods.

University of Michigan