Most immunotherapies, which aim to boost T cell activity, work poorly in treating estrogen receptor-positive (ER+) breast cancer. Targeting a different type of immune cell called macrophages could be a more effective approach, suggests a comprehensive new analysis of invasive ER+ breast cancers led by University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine scientists.

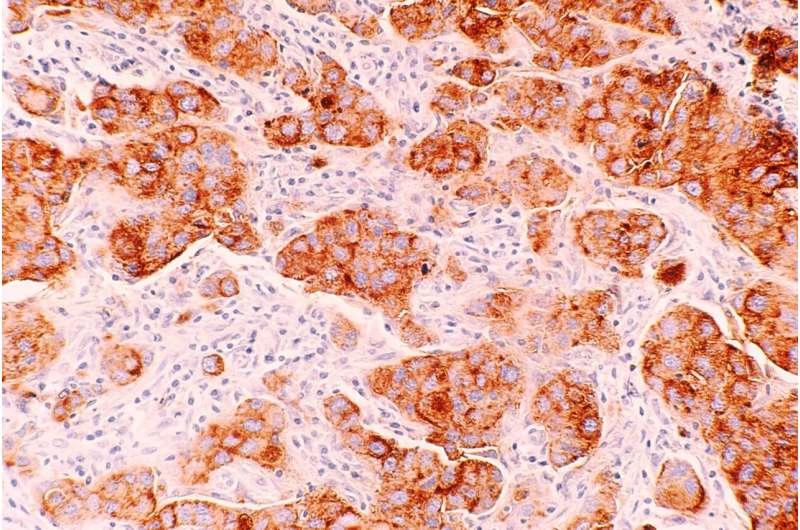

Published today in Nature Cancer, the study found that macrophages were the dominant immune cell infiltrating ER+ invasive lobular carcinoma (ILC) and invasive ductal carcinoma (IDC) tumors. Detailed spatial analysis of tumor regions also revealed distinct immune cell “neighborhoods” associated with good patient outcomes.

“In the past, IDC and ILC were lumped into the same category and treated as the same disease. But in the last few years, strong evidence has emerged that that they are, in fact, distinct diseases,” said lead author Sayali Onkar, Ph.D., currently a senior scientist at Mount Sinai Icahn School of Medicine, who did this research as a graduate student at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine. “We discovered important similarities and differences in the immunological landscape of IDC and ILC, suggesting that tailored immunotherapies are needed to target these diseases.”

Immunotherapies help the immune system to better recognize and destroy cancer cells. While powerful treatments for many cancers, including melanoma and lung cancer, immunotherapies tend to be less effective against most breast cancer subtypes—as reviewed in a recent Cancer Discovery article led by Onkar and Neil Carleton, a student in the Medical Scientist Training Program at Pitt.

“Breast cancers, particularly those that are ER+, don’t respond well to immunotherapy, so there is a huge unmet need for new therapies,” said co-senior author Dario Vignali, Ph.D., distinguished professor and interim chair of the Pitt School of Medicine Department of Immunology and associate director for scientific strategy and co-leader of the Cancer Immunology & Immunotherapy Program at UPMC Hillman Cancer Center.

“By testing our hypothesis that IDC and ILC differ in their immune response, we can inform where we should focus attention for development of novel approaches.”

The research was possible due to a collaboration between Vignali and co-senior author Steffi Oesterreich, Ph.D., co-leader of the Cancer Biology Program at UPMC Hillman and professor at the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine’s Department of Pharmacology & Chemical Biology, who have special expertise in cancer immunology and breast cancer biology, respectively.

By analyzing the tumor microenvironment—the complex ecosystem of cells, blood vessels and molecules surrounding a tumor—of patient samples, the researchers found that macrophages were the most common immune cell in both ER+ ILC and IDC, but they were especially prominent in ILC.

“To improve outcomes for patients with these diseases, we need to identify druggable targets focusing on macrophages,” said Oesterreich, who also holds the Shear Family Endowed Chair in Breast Cancer Research and is co-director of the Women’s Cancer Research Center, a partnership between UPMC Hillman and Magee-Womens Research Institute. “There is a huge lack of macrophage-targeting immunotherapies in development—the vast majority focus on T cells.”

Next, the researchers used state-of-the-art technology to analyze the spatial location of macrophages, T cells and other immune cells throughout the tumor. They identified unique cellular “neighborhoods,” or clusters of cells, in IDC and ILC tumors.

In IDC, one type of neighborhood dominated by macrophages and CD8+ T cells was associated with increased disease-free survival in patients, suggesting that these immune cells work together to kill cancer cells.

“These findings tell us that zooming out to look at the architecture of the tumor and understanding how immune cells influence each other, rather than simply looking at overall quantities of cells, is important,” said Onkar. “Targeting cellular neighborhoods within the tumor microenvironment could have a meaningful impact on patient outcomes.”

Looking at the types of macrophages inhabiting the tumor microenvironment, the team found that ILC had more tumor-promoting M2-like macrophages and fewer tumor-fighting M1-like macrophages than IDC.

According to the researchers, the study provides an important resource for future research toward developing novel immunotherapies or targets that focus on macrophages. Removing harmful M2-like macrophages or reprogramming them to become M1-like macrophages could be promising avenues for ILC treatments, and better understanding of the partnership between macrophages and T cells in ER+ breast cancer could lay the groundwork for combination therapies in this disease.

University of Pittsburgh