A recent study makes it clear: Countries like Sweden that can link data from different areas—such as the labor market and health care—have a decisive advantage when it comes to setting targeted actions.

A research team from the Complexity Science Hub, together with scientists from Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands, investigated the extent to which mental and somatic illnesses influence integration into the labor market and whether there is a difference here between refugee and Swedish-born young adults.

“In total, we analyzed data from 41,516 refugees and 207,729 Swedish-born people aged 20 to 25 from 2012 to 2016,” explains Jiaying Chen of the Complexity Science Hub and the Medical University of Vienna.

Multimorbidity is a risk for unemployment

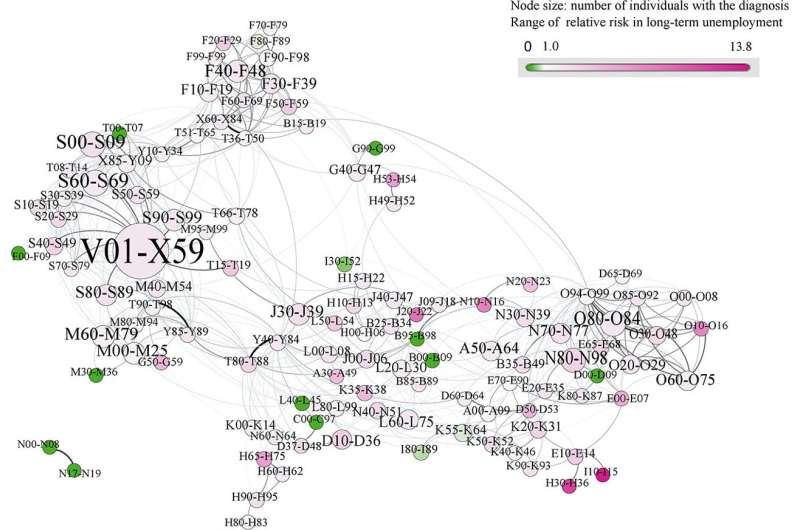

In both groups, multimorbidity (the simultaneous presence of several disorders) has a negative impact on labor market opportunities. Both mental and somatic disorders pose a risk that labor market integration will not succeed.

However, this effect is more pronounced among young refugees. They have a higher risk of being and remaining unemployed than those born in Sweden. However, the strongest risk factor for long-term unemployment is refugee status per se, the study finds.

Already more severely affected at the time of diagnosis

In addition, refugees have a lower chance of receiving disability pensions. While 7.2 percent of young Swedes with mental disorders receive disability pension, only 5.5 percent of those who have had to flee benefit from it.

“This is a very robust result that has already been supported in many studies,” explains Peter Klimek of the Complexity Science Hub. “It suggests that refugees, who have often experienced massive trauma, are at risk of poorer access to the health care system. This implies that they often need to have a higher level of severity before a disease is diagnosed,” Klimek says.

Poorer labor market integration can therefore also be exacerbated by the fact that poorer health already exists at the time of diagnosis, he adds. “With targeted public health actions to specifically address this group and to sensitize treating physicians, Sweden could bring about an improvement in the situation,” explains Ellenor Mittendorfer-Rutz from the Swedish Karolinska Institutet, who coordinated the project.

The trump card: An expanded data landscape

In other countries like Austria similar findings could not be obtained at all. Due to different social and health care systems, as well as different origin areas of refugees, the results of this study describe the situation in Sweden. However, they can only be transferred to other countries to a limited extent.

A good data infrastructure for research purposes is crucial. In Sweden, Finland and Denmark, there are already developed registry landscapes that allow, for example, de-identified information on health, labor market integration and refugee status to be centrally linked and securely evaluated. This enables researchers to analyze the interplay of these three factors.

Targeted measures

The findings support decision makers to take action to improve the situation where appropriate—such as implementing strategies to promote the inclusion and participation of young refugees in the labor market, reducing social disadvantage within the refugee population, and potentially improving the economic stability of these countries.

“In Austria, a similar study could not be conducted. On the one hand, there is a lack of complete data. For example, there is no diagnosis recording in the private practice sector. And on the other hand, data are pseudonymized differently in various areas, which is why they cannot be linked,” Klimek explains.

The findings are published in the journal Frontiers in Public Health.

Complexity Science Hub Vienna