Many cancer patients undergo treatment with multiple drugs, each of which attacks cancer in a different way, so the combination fights cancer on many fronts. But more drugs mean higher risks of side effects.

“Most cancer therapy is now a combination treatment,” says Avinash (Avi) Sahu, Ph.D., assistant professor at The University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center. Sahu joined UNM from Harvard and Dana-Farber Cancer Institute. “We wanted to find drugs that could suppress two cancer-causing pathways at the same time.”

But instead of spending hours in a lab, Sahu turned to his computer.

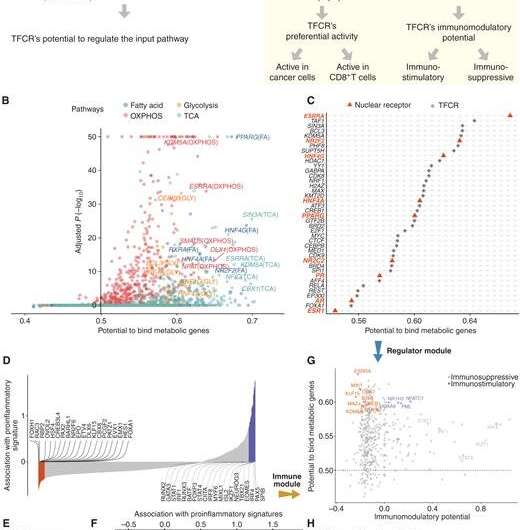

Sahu and his research team created two approaches. The first, called BiopotentR, uses publicly available genomic data to find drugs that can attack cancer in multiple ways and identify genes that the drugs target. The second applies machine learning methods to this information to predict how people will respond to immunotherapy. Their work is published in Cancer Discovery.

Machine learning is similar to the way people learn. Just as people learn new things—such as riding a bike or driving a car—through lots of experience, computer-driven machine learning assimilates vast amounts of data and gleans patterns that it can then apply to other tasks.

But cancer research data alone wasn’t enough for Sahu and his team to predict how people would respond to a drug. They needed additional biological data that they could then apply to cancer patients and cancer drug responses. In machine learning terms, they needed to learn from the biological context and apply that knowledge to a cancer context; it’s a technique called transfer learning.

Sahu and his team partnered with a company to find a compound that would target the top cancer gene candidate they identified using BipotentR. In preclinical testing, they confirmed that their predictions were accurate.

But the work can be expanded, Sahu says.

“When tumors have overactive multi-functional drug targets, patients are less likely to respond to immunotherapy,” he says. “However, patients with these types of tumors could potentially benefit from a combination of immunotherapy and multi-functional drugs.”

The team’s work is not limited to just metabolism and immune targets; it can be tailored to explore any two factors to find better multi-purpose drugs. Sahu says this approach thus presents an exciting opportunity for new research in a variety of cancer-focused projects.

And faster drug discovery means more accurate personalized medicine.

Michele W. Sequeira, University of New Mexico Comprehensive Cancer Center