Substance use disorder affects 20 million Americans, and more than 100,000 people died from a drug overdose in 2021, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. While the medication methadone has the strongest evidence-based effectiveness to prevent relapse, about half of patients drop out of their treatment within one year of initiation. The solution could lie in taking a simple “sugar pill” or placebo along with the methadone, according to a randomized clinical trial led by researchers at the University of Maryland School of Medicine.

In a randomized clinical trial published today in JAMA Network Open, lead author Annabelle Belcher, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, and her colleagues found that knowingly taking a placebo along with methadone could increase patients’ chances of staying on their treatment and provide other benefits like improved sleep.

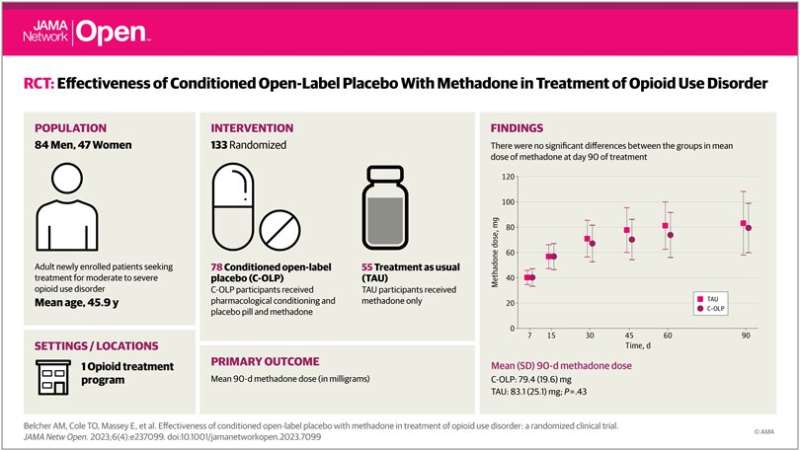

To conduct the study, the researchers enrolled 131 patients seeking new treatment for moderate-to-severe opioid use disorder. They were randomly selected to receive methadone (which needs to be dispensed daily in a clinic) along with a placebo pill or just the standard treatment of methadone. Patients selected for the placebo group were told they would be put on a placebo along with the methadone and were initially informed about studies showing the possible benefits of taking placebos to relieve symptoms such as pain and depressed mood. Clinicians in the study were not told which patients were taking placebos and which were getting the methadone alone.

After three months of follow-up, 78% of the placebo-treated group remained on methadone compared to 61% of the group that did not receive a placebo. The placebo group also reported better sleep quality.

“The clinical implications of our intervention have great potential impact, as retention in treatment is a serious challenge for the field of addiction medicine,” said Dr. Belcher. “We’ve demonstrated it’s feasible to administer a placebo in addition to standard-of-care methadone in a community-based opioid treatment setting without adding a significant burden to clinic procedures; the low-cost, low-risk nature of this intervention could provide an appealing strategy to target early methadone treatment adherence.”

Of the available federally-approved medications that are prescribed to treat opioid use disorder, methadone possesses the largest evidence base for long-term positive treatment outcomes, including decreased drug use, decreased crime and increased positive health outcomes. The medication can also cause side effects, like constipation and nausea; it also requires patients to come to a clinic each day to get their dose from a medical provider.

“We see the very real problem of retention all the time in our clinical work,” said study co-author and Eric Weintraub, MD, Professor of Psychiatry and Director of the Division of Addiction Research and Treatment at UMSOM. “There are many factors that get in the way of people’s ability to stay in treatment, including the fact that due to its bioavailability, clearance and half-life, methadone dosing requires a necessarily slow induction process. This means that it could take weeks before a person arrives at a therapeutic dose—a vulnerable time for our patients.”

It has long been assumed that deception or concealment is necessary for placebo effects to work—such as “tricking” a patient into believing an inert pill contains an active medication. But a growing body of evidence has found that placebos work even when patients know they are taking them. For example, a Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (BIDMC) clinical trial published in 2021 found that patients with irritable bowel syndrome who were knowingly treated with a placebo had a significant reduction in their gastrointestinal symptoms.

“Previous assumptions that placebo treatment needs concealment or deception to ‘work’ are not true,” said study senior author Ted Kaptchuk, director of the Program in Placebo Studies and the Therapeutic Encounter at BIDMC and professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. “Additionally, there is growing evidence that open-label placebo demonstrates similar neurotransmitter engagement to double-blind and deceptive placebos. It is important to note that a patient-clinician relationship is an important component of open-label placebo.”

UMSOM faculty members Emerson M. Wickwire, Ph.D., Professor of Psychiatry, Aaron D. Greenblatt, MD, Assistant Professor of Family & Community Medicine, and Laurence Magder, Ph.D., Professor of Epidemiology & Public Health were co-authors on this study. Faculty at University of Maryland, Baltimore’s School of Pharmacy and School of Nursing were also involved in this study as were faculty at the University of Maryland, College Park. Other co-authors included those from the National Institute on Drug Abuse and the NYU Grossman School of Medicine.

“Here in Maryland, the rate of drug overdose deaths has more than doubled in the past five years, among the highest increases of any state in the nation,” said UMSOM Dean, Mark T. Gladwin, MD, who is also Vice President for Medical Affairs, University of Maryland, Baltimore, and the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor. “This research demonstrates the important role that brain mechanisms play in adherence to medications for opioid use disorder. Based on this study, it appears that we could see immediate benefits from implementing placebos into clinical practice.”

University of Maryland School of Medicine