Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center identified a novel cell signaling pathway that potentially could be targeted in therapy for patients with aggressive pancreatic cancers.

In laboratory studies with human pancreatic cancer cell lines and genetically engineered mouse models of pancreatic cancer, the investigators discovered that the High Mobility Group A1 (HMGA1) protein functions as a “molecular switch” that “flips on” genes required by tumor cells to grow in an uncontrolled fashion and form invasive tumors.

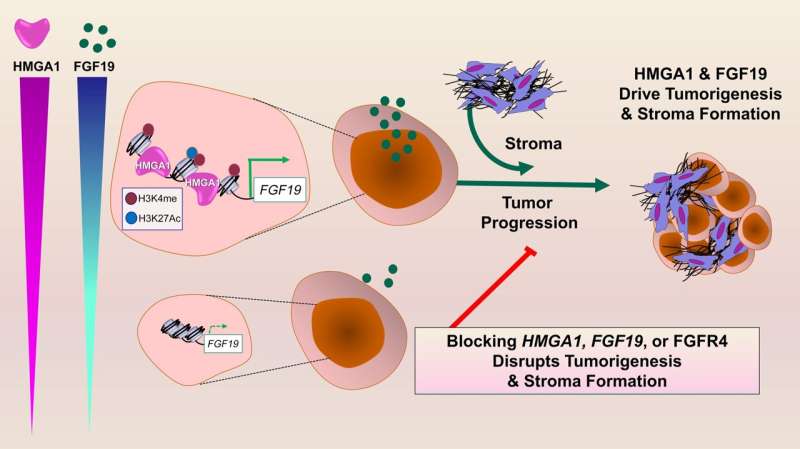

One of these genes activated by HMGA1 leads to the production of fibroblast growth factor 19 (FGF19), which is secreted by tumor cells. FGF19 not only provides signals that coax tumor cells to grow rapidly and invade surrounding tissues, but both HMGA1 and FGF19 cooperate to “build” a dense, fibrous, scar-like wall around the tumor cells, which is known as the stroma. Pancreatic tumors are among a few tumors that form a dense stroma, and the stroma is thought to create a barrier preventing therapy from reaching the tumor cells.

When the scientists silenced HMGA1 or disrupted FGF19 signals in mouse models of pancreatic cancer, tumor cells had markedly decreased growth and less stroma formation, suggesting that drugs to block FGF19 signals already available for use by patients with other diseases could be repurposed to treat pancreatic tumors that have high levels of FGF19. Studies of cancer genomes indicate that up to a quarter of human pancreatic cancers have high levels of HMGA1 and FGF19.

A description of the work was published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

“Pancreatic cancer is among the most recalcitrant tumors, for which there really are no effective therapies,” says senior study author Linda Resar, M.D., professor of medicine, oncology and pathology at Johns Hopkins. Many patients succumb to pancreatic cancer in six to 12 months of diagnosis, she says, and genomic data indicates that patients with pancreatic cancers with high levels of both HMGA1 and FGF19 have the worse outcomes with even shorter survival than that of other patients with pancreatic cancer.

“In prior work, we found that HMGA1 was overexpressed in most pancreatic cancers and very late stage precursor lesions, as well as in other aggressive tumors such as leukemia and advanced stage myeloproliferative neoplasms, which suggested to us that HMGA1 was playing a fundamental role in driving tumor progression,” Resar says.

In a series of laboratory experiments, Resar and colleagues investigated several methods of disrupting HMGA1 and FGF19. First, they silenced HMGA1 in pancreatic cancer cell lines from primary and metastatic tumors using short hairpin RNA—or artificial RNA molecules that block gene expression—and observed that a deficiency in HMGA1 led to decreased growth rates, impairing migration, invasion and other cancerous properties.

They also developed mouse models of pancreatic cancer missing one or two mouse genes for HMGA1 in the pancreas. Surprisingly, loss of just one gene was sufficient to slow tumor formation and progression.

In additional tests, researchers found that FGF19 gene expression, protein levels in pancreatic cancer cells and secretion all depend on HMGA1. Also, silencing FGF19 mirrored effects of silencing HMGA1, decreasing tumor growth and invasive properties. Most importantly, administration of BLU9931, a small-molecule drug that inhibits FGFR4 (a receptor for FGF19), led to decreased tumor growth and stroma formation in mouse tumors.

“Together, we discovered what we believe is a previously undescribed paradigm whereby tumor cells collaborate via HMGA1 and FGF19 to drive cancer progression and stroma formation,” Resar says. “This work also unveiled FGF19 as a potential therapeutic target for a very aggressive subset of human pancreatic cancers. Perhaps the most exciting aspect of our studies is that inhibitors to FGF19 are available and have already been tested in humans.”

In ongoing studies, the researchers are evaluating additional tumors to determine if they upregulate FGF19 and could benefit from treatment with FGF19 blockade. The researchers will also test whether inhibiting FGF19 blocks the spread or metastasis of tumor cells to distant sites.

Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine