Dangers like working high above the ground or with heavy machinery are common hazards for laborers in industries like construction or excavation. But there’s another near-universal hazard for laborers—heat.

Margaret Morrissey, a postdoctoral fellow within UConn’s College of Agriculture, Health and Natural Resources and president of occupational safety for the Korey Stringer Institute, led a recently published study that found heat is the number one cause of exertion-related injuries and fatalities on U.S. work sites.

This work was recently published in the International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health.

Using data reported to OSHA (Occupational Safety and Health Administration), the team found that of all injuries and fatalities, about 3% were exertion-related. Of that 3%, a staggering 89% were related to heat stress.

This study shows that heat is a significant danger for laborers in industries like construction, excavation, farming, and assembly line workers. Morrissey says she hopes this study can help improve health and safety measures to protect workers.

“We want people to recognize heat is a problem and it might not be one people automatically think of,” Morrissey says.

There is a body of scientific literature examining exertion-related injuries and fatalities among athletes and soldiers. But until now, no one had conducted a similar study for laborers.

“We really don’t have a good idea of what that looks like in the laborer population,” Morrissey says.

The data may also be underreporting exertion-related injuries and fatalities. The data employers report to OSHA is limited to events that happen at the work site, meaning it does not include when someone suffers an injury or fatality related to on-the-job heat stress elsewhere.

Additionally, some heat-related illnesses treated on-site, with simple measures like hydration and body-cooling, are not included in OSHA data.

Based on how OSHA asks employers to classify the cause of an injury or fatality, events that may have been related to heat are attributed to another cause.

“Not only are we seeing predominantly heat-related fatalities and injuries for exertion-related events, but we’re thinking this is underreported too,” Morrissey says. “The problem may be a lot bigger than we originally anticipated.”

Morrissey emphasizes that heat-related injuries and fatalities are preventable. There are simple, low-cost measures employers can take to protect workers in hot conditions, like hydration, body cooling, environmental monitoring, and educational training. Employers can also engage workers in heat acclimatization, which gradually exposes workers to hot conditions, allowing them to adapt to better tolerate heat and decrease their risk of injury.

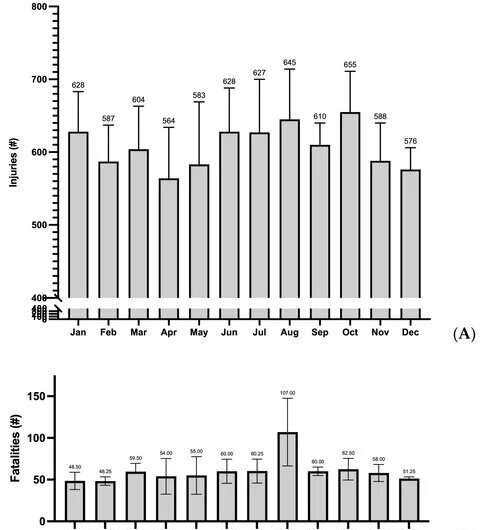

In this study, the researchers also found that there were more injuries and fatalities in the summer months. But they do not know why this is the case—if it was due to increased heat, or another factor, like the fact that there are usually more workers on site in the summer months. Morrissey says they plan to investigate this pattern further.

Morrissey says she also wants to look at the temperatures on days with reported incidents, since events like cardiac arrest, kidney strain, and cognitive impairment may be caused by heat.

“Whenever we think of heat stress, a lot of people only think of heat-related illnesses,” Morrissey says. “But in reality, there’s so many different things that heat can cause.”

Anna Zarra Aldrich, University of Connecticut