A new study has identified critical gaps in care for people with Parkinson’s disease (PD) in the U.S., including disparities affecting women, people of color (those who identify as Asian, Black, Hispanic and Native American), and residents of rural areas. Published in the scientific journal npj Parkinson’s Disease, the peer-reviewed analysis utilizes 2019 U.S. Medicare data to examine demographics, service utilization patterns, and disparities in care access for people living with PD.

“By utilizing 2019 Medicare data that represents 90% of people living with Parkinson’s in the U.S., this research provides the most timely and comprehensive study of patients with PD yet conducted,” said James Beck, Ph.D., senior author of the study and chief scientific officer for the Parkinson’s Foundation. “These findings underscore the need for better training of general neurologists and other care providers treating people with PD.”

The large study population also allowed for a deeper analysis of inequities in care for subgroups historically excluded from PD research. The study is a collaboration between the Parkinson’s Foundation, NORC at the University of Chicago, The Michael J. Fox Foundation for Parkinson’s Research (MJFF), and co-author Allison Willis, MD, MS, MDS, an associate professor of Neurology at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania.

The key findings include:

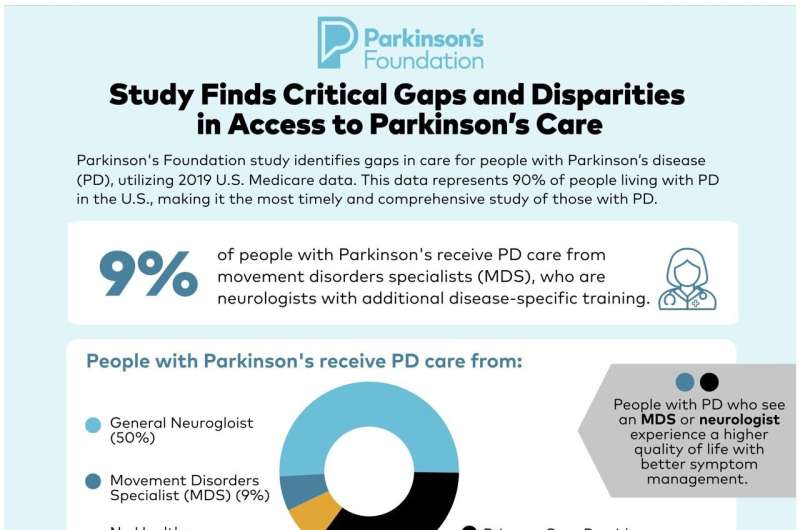

- Only 9% of people with PD received care from movement disorder specialists (MDS), expertly trained neurologists who can recognize PD’s distinct nuances and tailor treatments to each patient.

- Of the remainder, 50% of people with PD received care for the disease from general neurologists, and 29% received PD care from primary care providers.

- Care access disparities persist for women, people of color, and residents of rural areas—each possibly facing challenges receiving diagnosis and treatment.

- Although depression affects 53% of people with PD, approximately 2% received treatment from a mental health professional.

- Utilization rates of supplemental therapies—including physical and occupational therapy, speech-language therapy, and mental health services—were low, with only 20% of people with PD seeing a physical therapist, for example.

“This impactful analysis reveals the significant gaps in access to both recommended and best practice care for PD,” said Willis. “Also, our scientific reporting and understanding of PD has focused on specialty center populations, which these data suggest are a minority of the PD population. Persons who are not accessing recommended or best practice care are likely to experience PD very differently.”

The decision to focus on data from 2019 stemmed from the desire to concentrate on care access patterns prior to the disruption in care access brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. The timeliness of the data provides a pre-COVID baseline, which could help inform future studies examining changes that took place during the pandemic.

“While a lot of work remains in order to provide expanded care services for people and families living with PD, this is a critical step in understanding the disparities in access to expert care across populations,” said Ted Thompson, JD, MJFF’s senior vice president of public policy. “Studies like this can paint a fuller picture on the public policy priorities that all people with PD and their families need to live a better quality of life with the disease.”

The Parkinson’s Foundation estimates that one million people in the U.S. are living with PD, and this number is expected to rise to 1.2 million by 2030. Currently, there are only 660 MDS in the U.S., with a total of six practicing in rural areas. There aren’t enough expertly trained specialists today for the growing population of people living with the disease.

A shortage of MDS can bring challenges in seeking care, including long appointment wait times and unreasonable travel distances. There are opportunities to improve access to specialized care by expanding PD-specific training for healthcare professionals and pursuing strategies that improve access across all population groups. These results will support policy development and future research that dives deeper into access issues faced by beneficiaries, especially those who may not live near the highest-trained specialists.

“Being able to work with a team of specialists who are knowledgeable about Parkinson’s disease has made a tremendous difference for me and my family,” said Richard Huckabee, who lives with PD and regularly sees an MDS and attends PD-specific exercise classes and support groups. “Whether you’re newly diagnosed or have been living with PD for a while, I encourage you to seek the support you need so you can live better with PD.”

Parkinson’s Foundation